Watershed Movements

Watershed Movements is a unique initiative designed to study the relationship between embodied art practice, storytelling, river health, and participant well-being. Water stories will be collected from community members living along the banks of the Raquette and Genesee Rivers in New York, followed by participation in an embodied art activity. Participants will be surveyed before and after the study. The Raquette River watershed is a focal point for conservation initiatives and biodiversity preservation, while the Genesee River watershed is comprised of more urban land use, connecting a number of smaller upstream towns and cities of central NY with Rochester near the river’s outlet into Lake Ontario.

Watershed Movements is designed to measure the correlation between perceptions of the state of human health and river health, in addition to measuring if participation in storytelling and/or embodied practice make a difference in those perceptions.

This virtual exhibit is the educational supplement to the project, with a focus on river health, human health, and their intersections.

Hewitt Lake, NY (A. Gluckman)

Hewitt Lake, NY (A. Gluckman)

Watershed Movements is a project of EchoLab, sponsored through a Research Catalyst grant from the University of Rochester's Environmental Health Sciences Center and the Institute for Human Health and the Environment.

For additional information about this research or the other projects of EchoLab, go to www.echolab.art.

Methodology

Watershed Movements is designed to reflect the symbiotic relationship between human communities and waterways through education, research, and engagement by means of narrative and movement. The importance and uniqueness of this project lies in both the story collection methodology and the artistic translation of those stories as a form of qualitative data. The project involves a floating story collection booth that docks at popular sites along the Genesee and Raquette Rivers. Participants will be prompted to offer a "water story," which will be digitally mapped to the locations where they were collected, creating an interactive audio map that is accessible to the broader community. Along each river, the project will facilitate movement choirs. For the purposes of this project the movement choirs serve as an embodied art practice used to investigate whether art can foster a deeper

connection between the relationship between human health and the health of the river and watershed.

Check out the prototype for the Watershed Movements floating storytelling craft...

The storytelling vessel designed and created for Watershed Movements (A. Gluckman)

The storytelling vessel designed and created for Watershed Movements (A. Gluckman)

Definitions and Terms

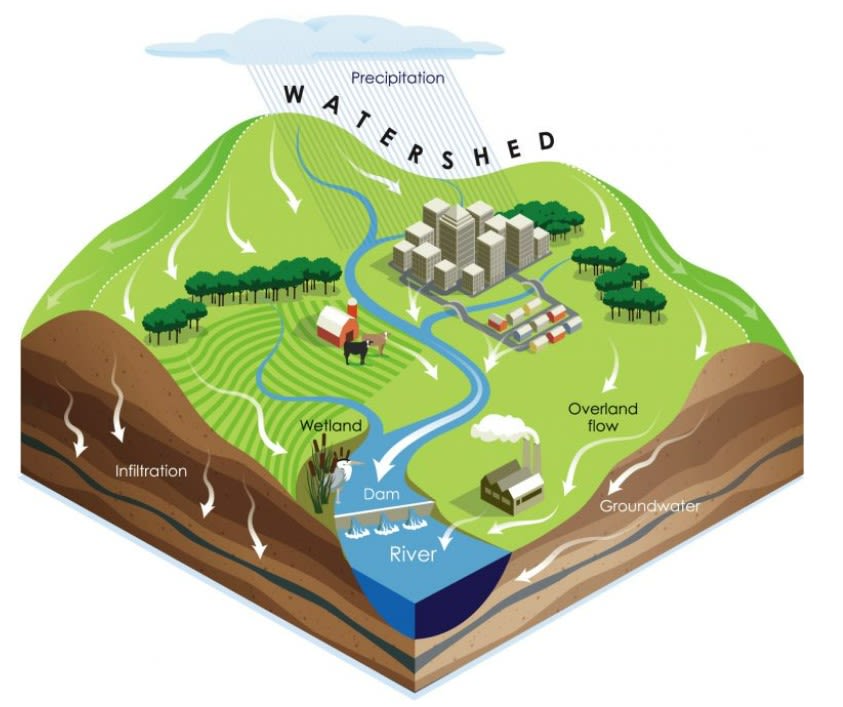

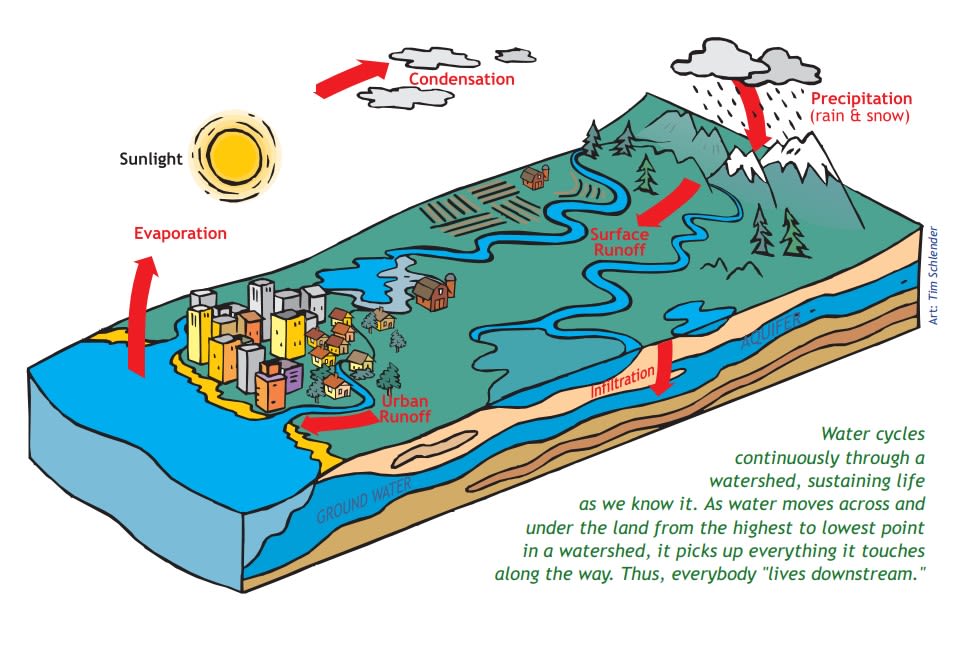

Watershed: "an area of land that drains all the streams and rainfall to a common outlet such as the outflow of a reservoir, mouth of a bay, or any point along a stream channel" (USGS)

River: natural freshwater stream that flows from higher elevations moving to a lower elevation in a channel with defined banks to a larger body of water.

Hydrology: "science that encompasses the occurrence, distribution, movement, and properties of the waters of the weather and their relationship with the environment within each phase of the hydrologic cycle" (USGS)

Ecosystem: a geographic area where plants, animals and other organisms, as well as weather and landscape, work together to form a bubble of life. Ecosystems contain biotic or living parts, as well as abiotic factors, or non-living parts.

Runoff: the water that is pulled by gravity across the land’s surface, replenishing groundwater and surface water as it moves into a river, stream or watershed.

Wetland: a low-lying area of land that is saturated with water, either seasonally or permanently, andsupports aquatic vegetation and hydric soils. Wetlands are distinct ecosystems that can be foundbetween dry land and deep water in lakes and streams.

Source: Be Water Friendly

Source: Be Water Friendly

What is river health?

River Health: A Complex Assessment

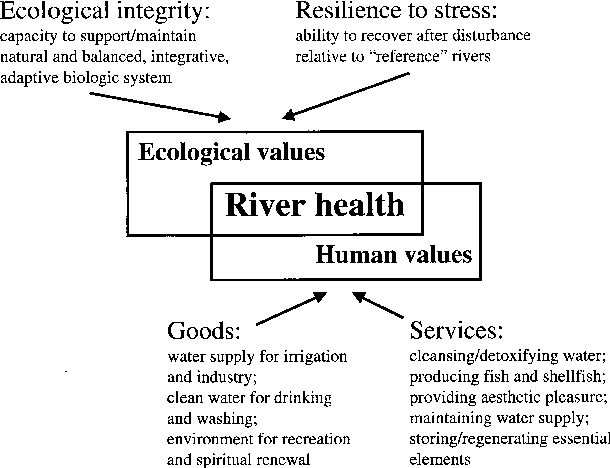

There are numerous metrics that are used to assess the health of rivers. One category of metrics address the natural function of rivers while the other category focuses on the social function of rivers. The natural function metrics speak to the health of the river itself and its ecosystem while the social function metrics address the utility of the river for human health and progress. The current thinking about river health seeks a middle ground between "ecological" and "human values," to determine sustainable and mutually-beneficial ways to steward rivers.

A. Boulton, "An overview of river health assessment: philosophies, practice, problems and prognosis"

A. Boulton, "An overview of river health assessment: philosophies, practice, problems and prognosis"

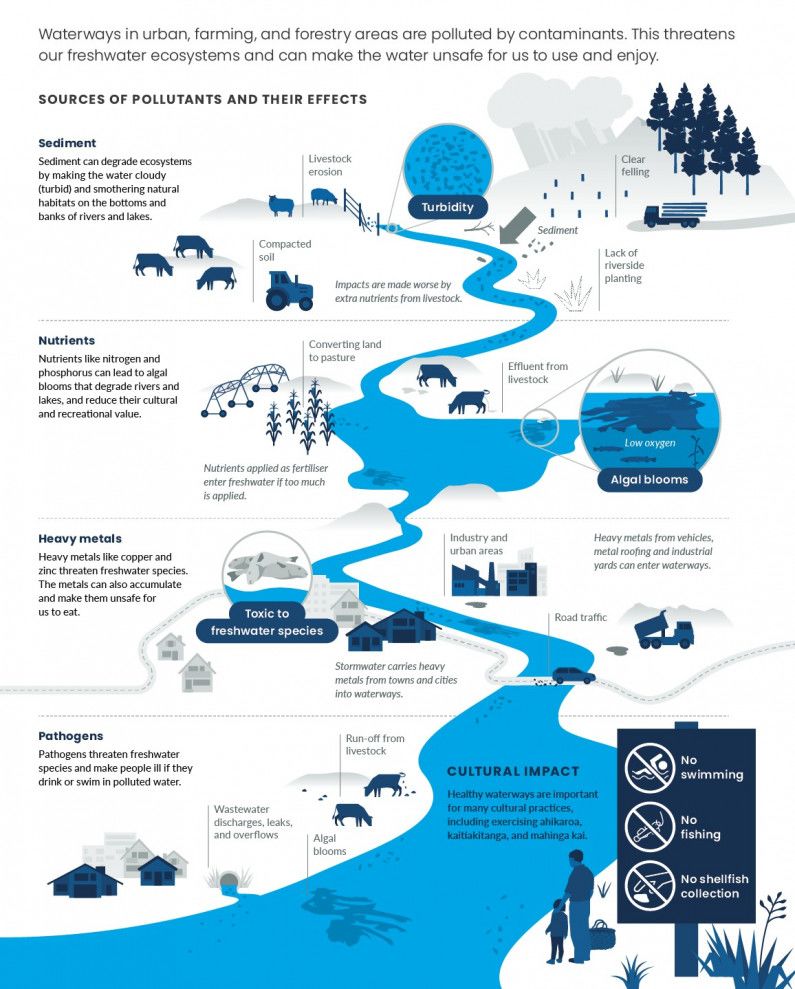

In this project, the metrics considered for measuring the natural function of rivers are the following three categories: water quality, flow, and biota.

Water quality refers to the condition and characteristics of water that determine its suitability for various uses and the health of waterways and their ecosystems. There are physical, biological, and chemical dimensions to water health in rivers and different types of metrics used to assess how they contribute to water quality.

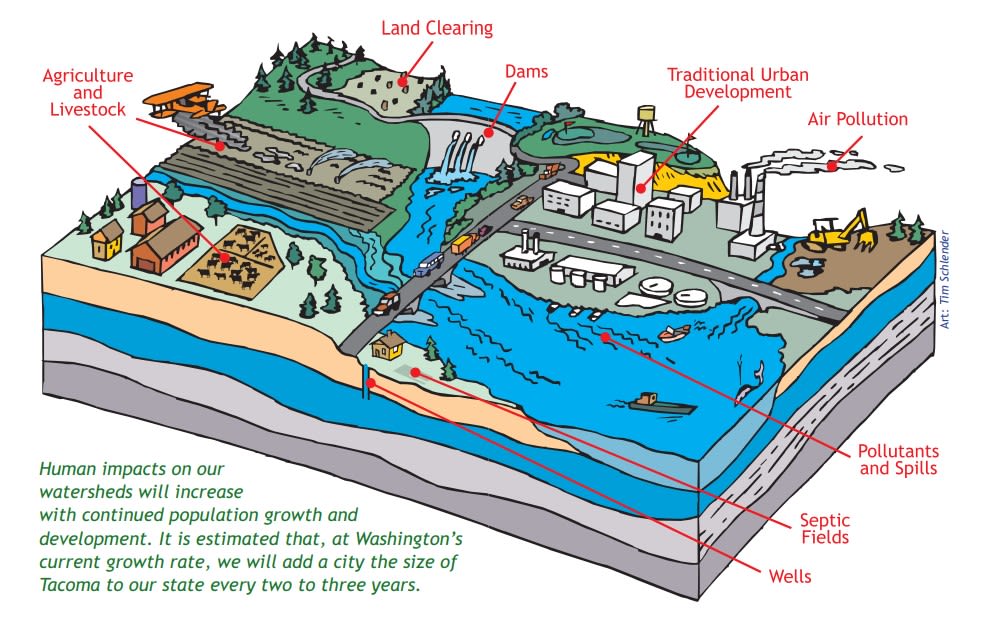

Multiple factors can influence water quality, including natural processes like weathering, erosion, and biological interactions, as well as human activities such as industrial pollution, agricultural runoff, and improper waste disposal. Contaminants commonly found in water include both organic and inorganic substances, pathogens, heavy metals, pesticides, and nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus.

Source: New Zealand Ministry of the Environment

Source: New Zealand Ministry of the Environment

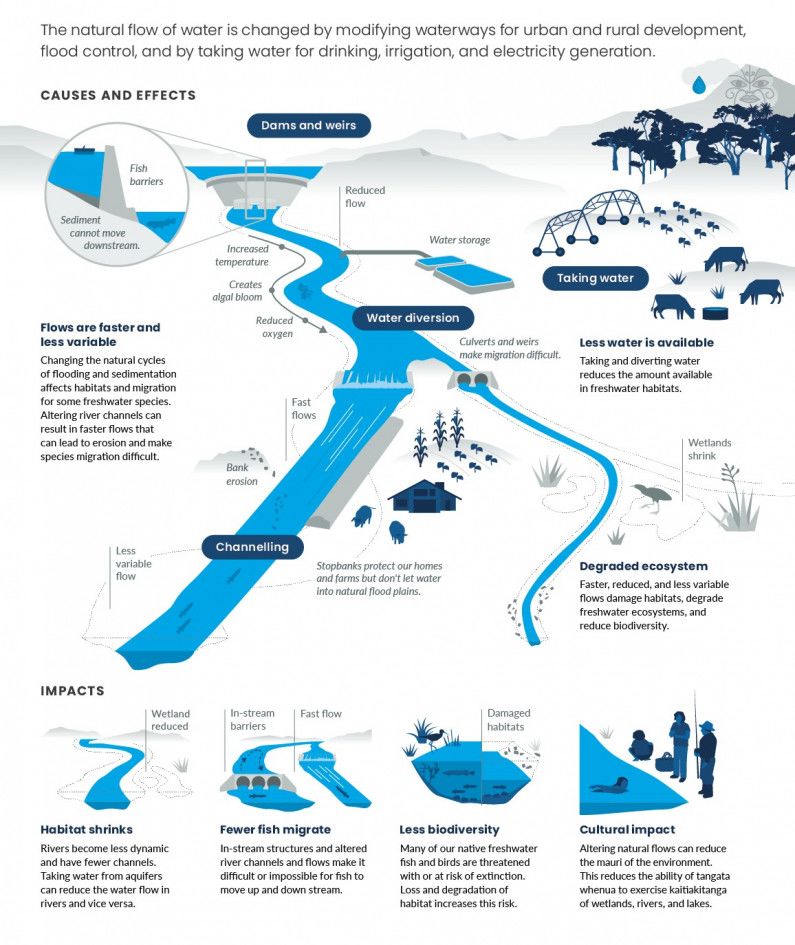

Flow is another category of indicators that help to measure the health of rivers. Included in this category are: streamflow , river morphology, connectivity , and catchment process.

Source: New Zealand Ministry of the Environment

Source: New Zealand Ministry of the Environment

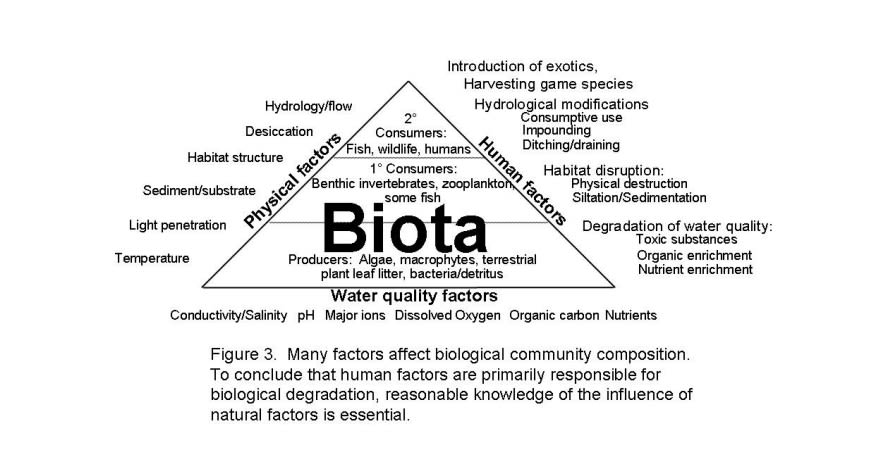

The last category of metrics for river health in this project is biota, which includes biodiversity, species composition, and habitat characteristics.

Source: Florida Department of Environmental Protection

Source: Florida Department of Environmental Protection

Human-Centered River Health: Social Functions and Metrics

Another way of thinking about and measuring river health involves assessing their utility for humans. The social function of rivers, therefore, defines the health of rivers through the lens of how well they serve human needs. Social uses of rivers include: individual and human health, agriculture and food security, hydropower, industry, transportation and shipping, recreation, and cultural applications.

The social function and uses of rivers for human benefit create unique challenges for rivers and their watersheds. Indeed, anthropogenic pressures present the greatest risk to healthy rivers and watersheds. Climate change, population growth, pollution, overexploitation of land, changes in flow (dams), and the multiple disruptions to ecosystems endanger rivers, watersheds, and all that live in them.

Certain measures of river health are interpreted through the lens of how well rivers address human needs, be it through providing drinking water or providing enough water for irrigating crops. The metrics related to the ability of rivers to serve humans is not necessarily the same set of metrics that determine a river's natural health. Both natural and anthropogenic causes have a negative impact on water quality in rivers and manifests differently in rural and urban areas.

Human Health and Rivers

A Complex Relationship: Human Health and River Health

Watersheds are a level of ecosystem that help provide for physical, mental and social human well-being. A well-managed watershed provides its inhabitants with benefits such as cleaner water, increased food and income security(e.g., fishing, farming), employment, recreational opportunities and greater protection from floods and droughts. Managing for health at a watershed scale offers the double dividends of improvements to both social and environmental determinants of health.

Perhaps the most powerful dynamic linking human health and water health is the water cycle itself, which demonstrates the inseparability of human action and consequence on waterways and watersheds. Everyone lives in a watershed. Everyone is affected by the water that runs through, under, and above the land.

Healthy rivers and watersheds are essential to human health. Individuals and community require access to healthy water for physical and mental health. Multiple studies have shown that the more that humans are near the water, the healthier they are as individuals and as communities.

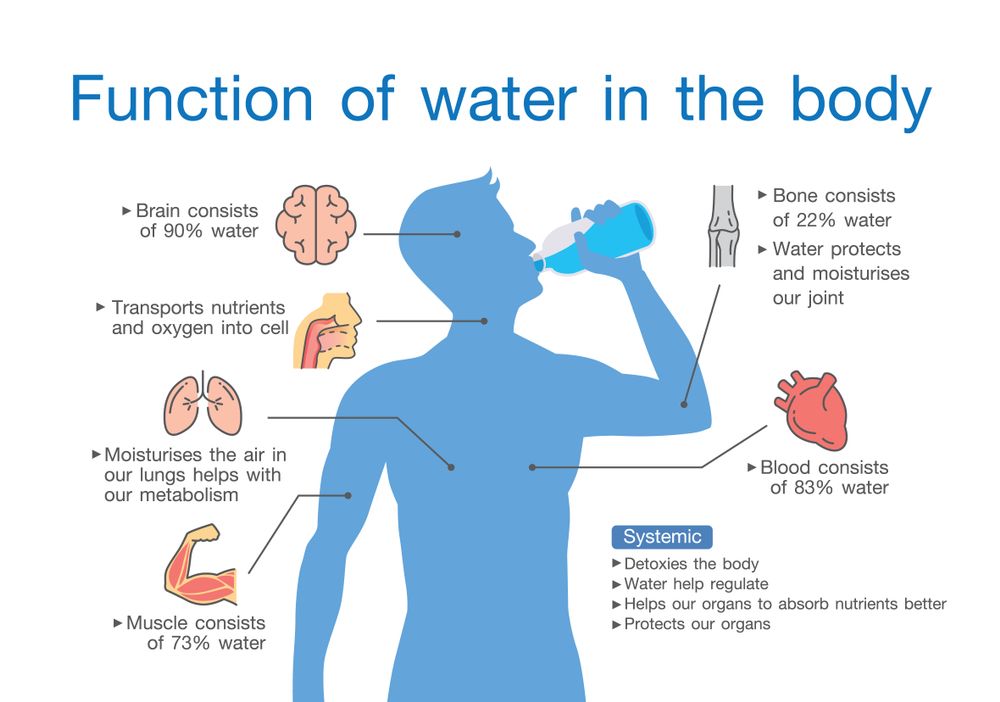

Physically, water is a necessity for human bodies, contributing to every major body process; life is not possible without water. And thriving is not possible with clean water.

Z. Cutlerywala

Z. Cutlerywala

Perhaps less known and understood is the impact of water on mental health--water as a biological process, but also the presence of waterways as a prime contributor to good mental health for individuals and communities. Being in proximity to a waterway has proven to elicit:

- Improved sense of well-being

- Reduced cortisol levels, heart rate, and blood pressure

- Feelings of connection, stability, and peace

- Enhanced feelings of creativity

- Improved mood

- Improved sleep

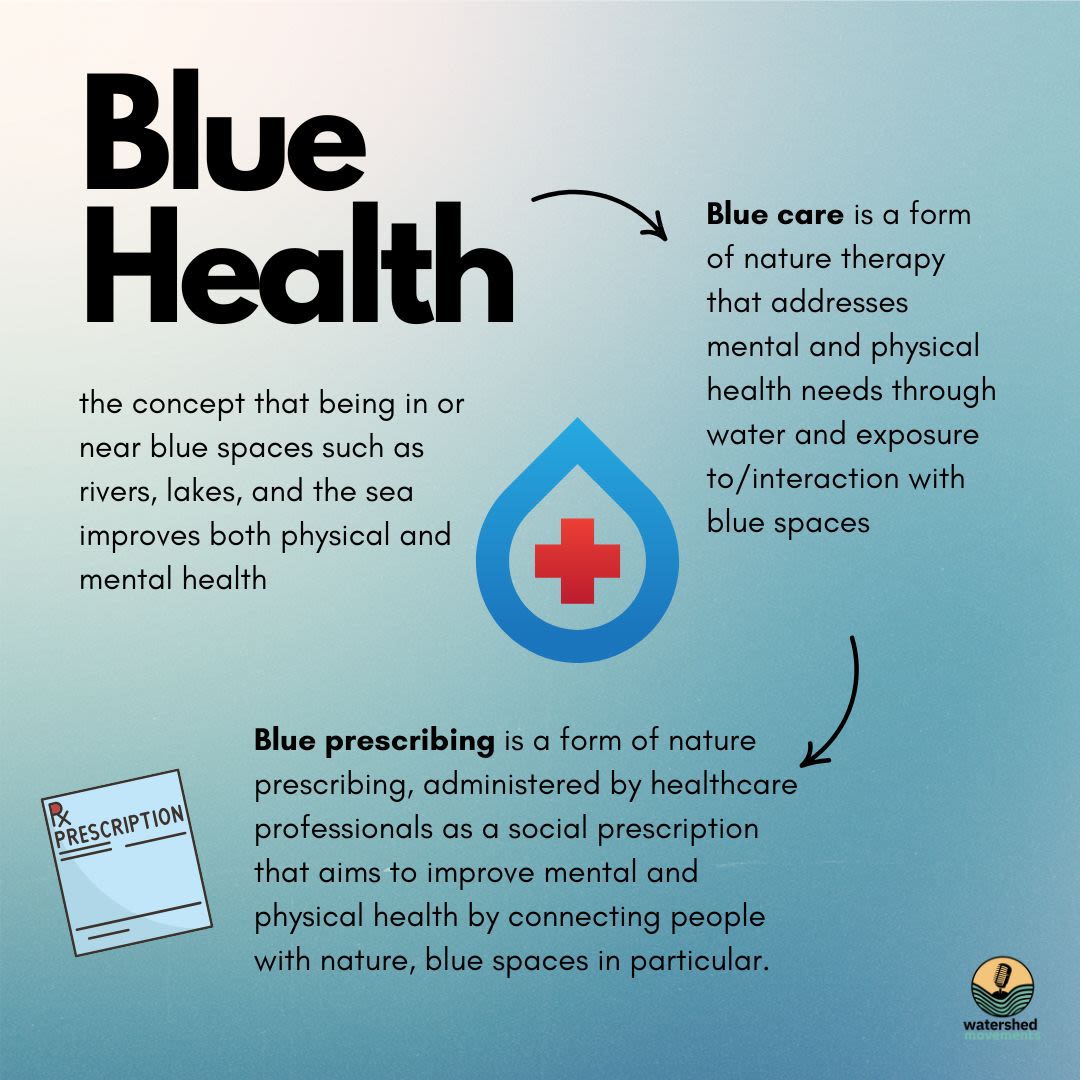

Indeed, a new term and way of thinking has emerged from this linkage, blue health. Research indicates that connectedness with and time spent in blue spaces positively correlates with better mental health outcomes.

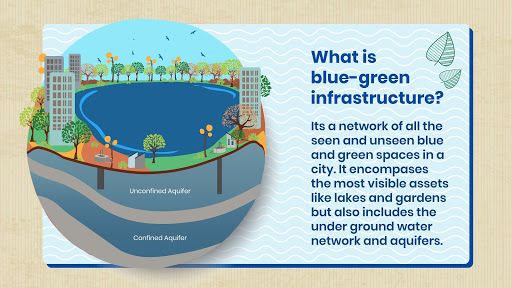

Blue spaces are being intentionally crafted by urban planners to take blue health into account. Blue infrastructure takes into account how the coast, rivers, and inland lakes can help tackle major public health challenges, such as obesity, physical inactivity, and mental health disorders. Green space and blue space are prioritized to optimize healthy lifestyles, social connectedness, environmental stewardship, and climate resilience.

An example of blue-green infrastructure by Well Labs

An example of blue-green infrastructure by Well Labs

The Genesee River

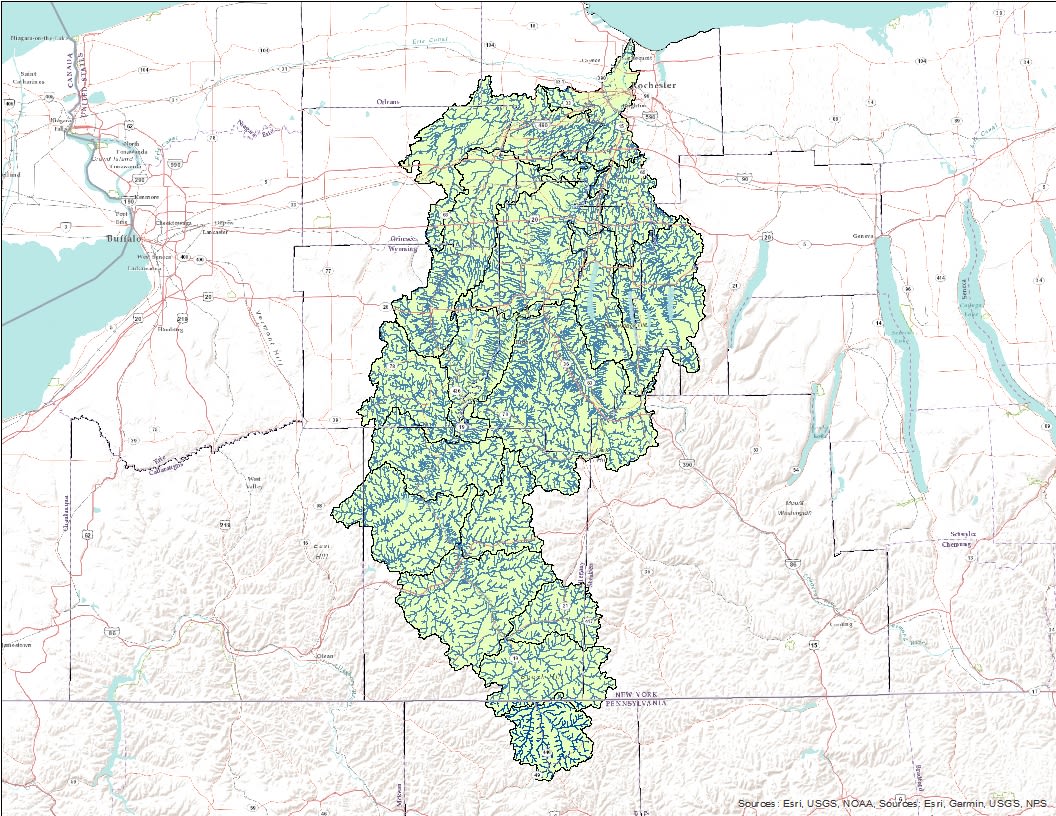

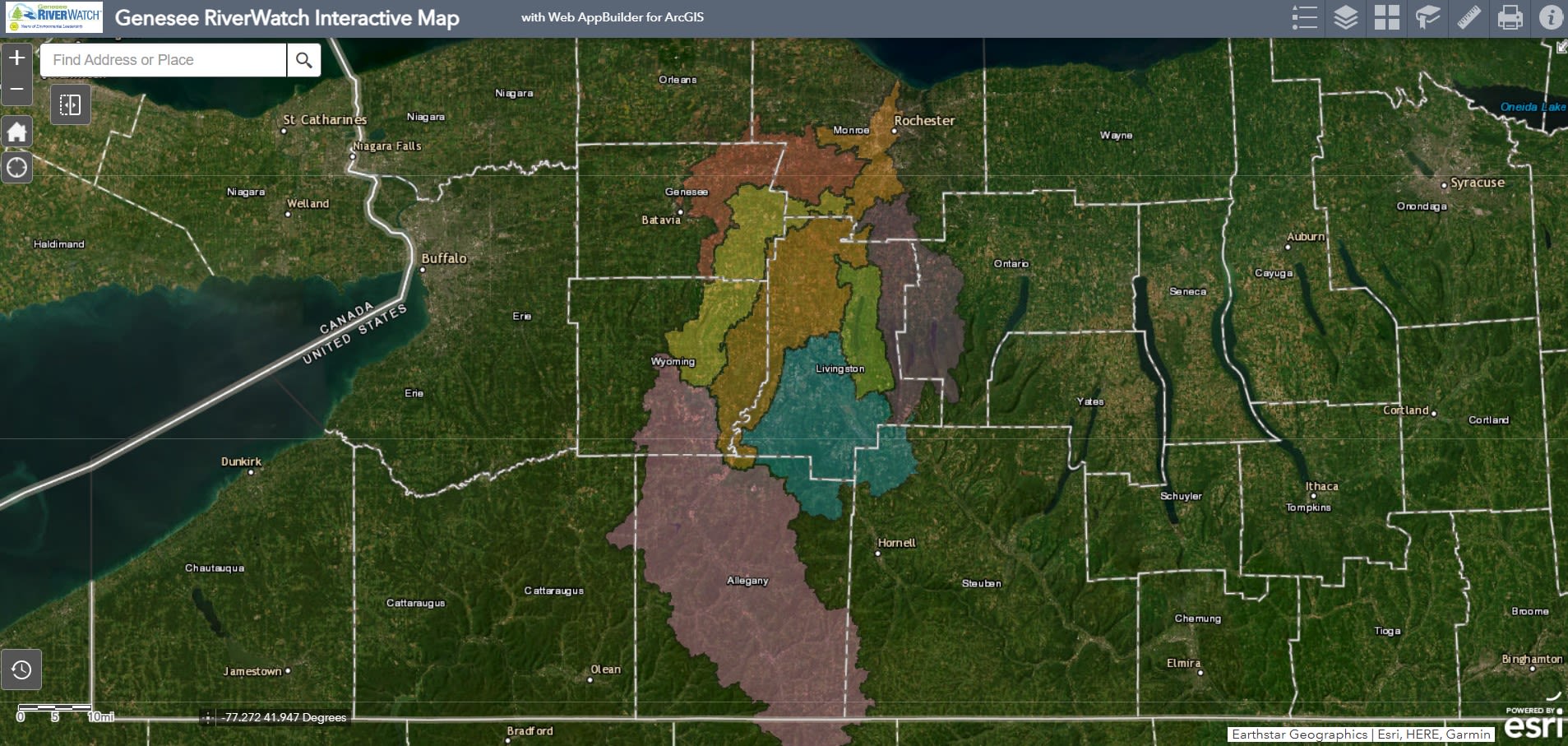

Map of the Genesee River Watershed

Map of the Genesee River Watershed

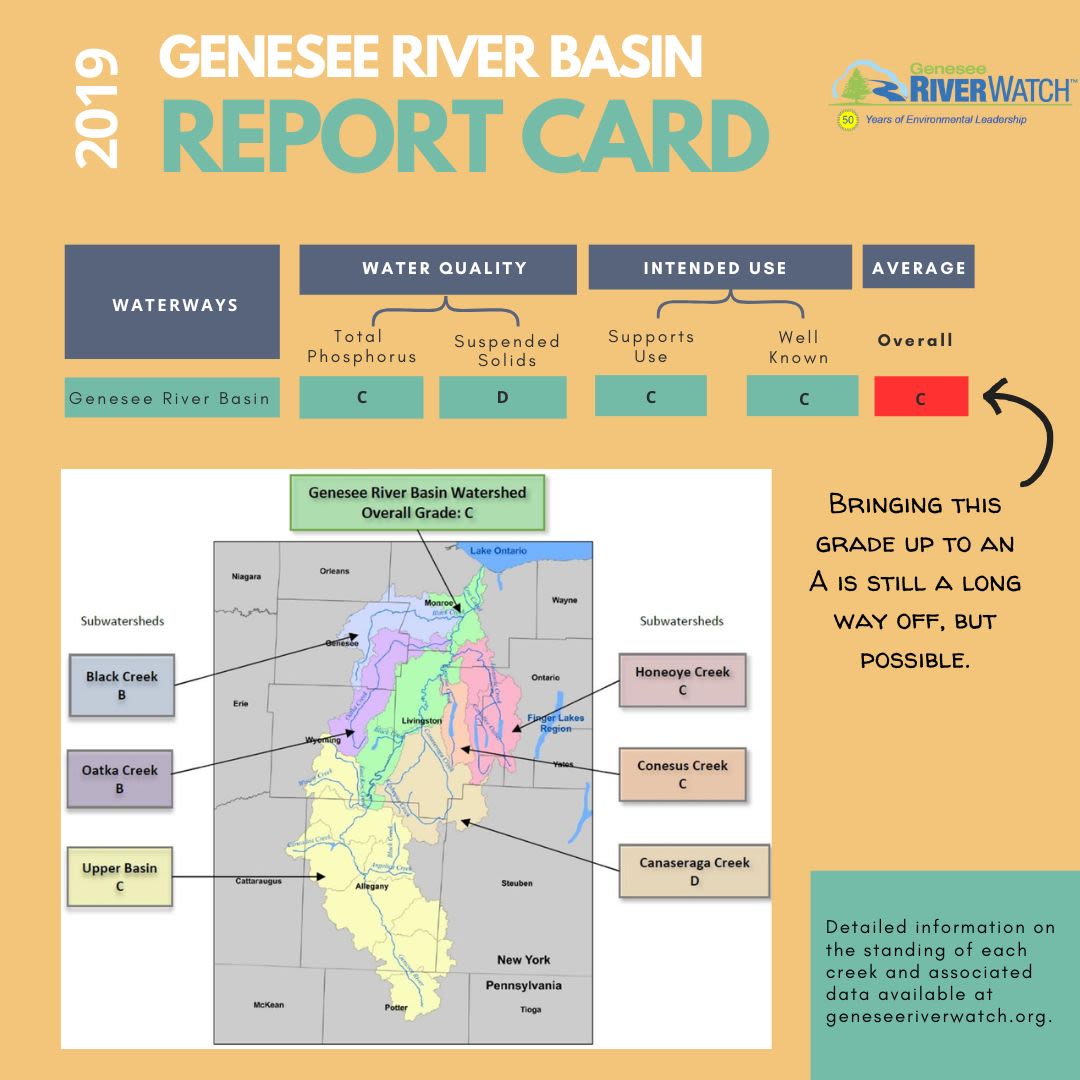

Genesee River Basin Report Card excerpt 2019

Genesee River Basin Report Card excerpt 2019

The "Pleasant Valley"

"Ge-ne-see" is a Haudenosaunee term meaning "pleasant valley," an apt term for the Genesee River and the whole of the watershed. The Onöndowa'ga:' use the name Gasgosago, "Place of Three Falls., and the Casconchiagon, "River of Many Falls," has also been used. The Genesee is the second longest river in New York, running south to north, 157 miles from the headwaters in Potter County, Pennsylvania to the mouth of the river emptying in Lake Ontario. Starting at an elevation of 2500 feet above sea level, the river drops through three sets of falls to 247 feet above sea level at Lake Ontario. The Genesee River receives drainage from about 2,500 square miles, including portions of Genesee, Livingston, Wyoming, Monroe, Allegany, Steuben, Ontario, Orleans, and Cattaraugus counties in New York, and Potter County in Pennsylvania.

Grading the Genesee

A comprehensive six-volume study of the water of the Genesee River was conducted by SUNY Brockport in 2013, assessing the major challenges for the river and watershed. In response, NYSDEC published the Nine Key Element Watershed Plan to deal with the most challenging findings, primarily an overabundance of phosphorus and sediment.

In 2019, the Genesee River Basin received its first ever report card, with a focus on water quality and usability of the Genesee River and its major tributaries. The overall grade was a C, with tributaries earning as high as a B and as low as a D. The report card, a project designed to create awareness of the environmental challenges facing the Genesee, showed that parts of the river are in good environmental health, but much work needs to be done to improve major portions of the watershed.

Major Challenges

The main challenges facing the Genesee River include: elevated levels of phosphorus, high degree of turbidity, streambank erosion, urban runoff, and legacy pollution.

Phosphorus poses the biggest challenge to the health of the Genesee. Phosphorus is an essential nutrient for plants and animals. However, excessive phosphorus in surface water can cause explosive growth of aquatic plants and algae. This can lead to a variety of water-quality problems, including low dissolved oxygen concentrations, which can cause fish kills and harm other aquatic life, a process called eutrophication. The majority of phosphorus in the Genesee River comes from agriculture, wastewater treatment plants, leaky septic tanks and urban runoff, and natural sources like eroding soil.

Streambank erosion contributes to a high level of sediment and suspended solids, which creates a high level of turbidity (also increased by high levels of phosphorus). High turbidity not only makes the water appear cloudy, but also decreases the oxygen content of the water and endangers all life in the water.

Urban runoff occurs when rainwater picks up trash, chemicals, sediment, and waste into streams, lakes, and groundwater. Legacy pollution in the Genesee is a serious contributor to unhealthy conditions in the watershed. Eastman Kodak, Friendship Dairies, and agricultural runoff have are among the worst offenders, although Kodak paid $15 million in 2019 to clean up the toxic metal pollution in the Genesee that has required dredging.

Solutions: Multi-Leveled Approach

The challenges to remediating the Genesee River and watershed are plentiful. Luckily, so are the proposed solutions and community commitment. There are recommendations at every level for how to created a healthier Genesee River and watershed--from the policy level regarding regulations to the community level regarding organizing to the individual level regarding behaviors and choices that prioritize water health. General recommendations include:

- Monitor water quality

- Upgrade and maintain infrastructure

- Improve stormwater management

- Upgrade wastewater treatment

- Lobby for more responsible industry practice

- Maintain healthy river banks and vegetation

- Cultivate a sense of stewardship

- Explore social connectivity of river

- Volunteer with local organizations supporting the river

- Advocate for policies that protect the river and its ecosystem

- Streambank restoration

- Support current community efforts to protect the water and create a communal role/groups as Waterkeepers/River Keepers/Guardians/Stewards

- Designate and develop populated land long Genesee as a protected blue

The NYSDEC offered a "9 Key Element Watershed Plan" in 2015, outlining specific strategies to mitigate the two biggest challenges to the river--phosphorus and sediment.

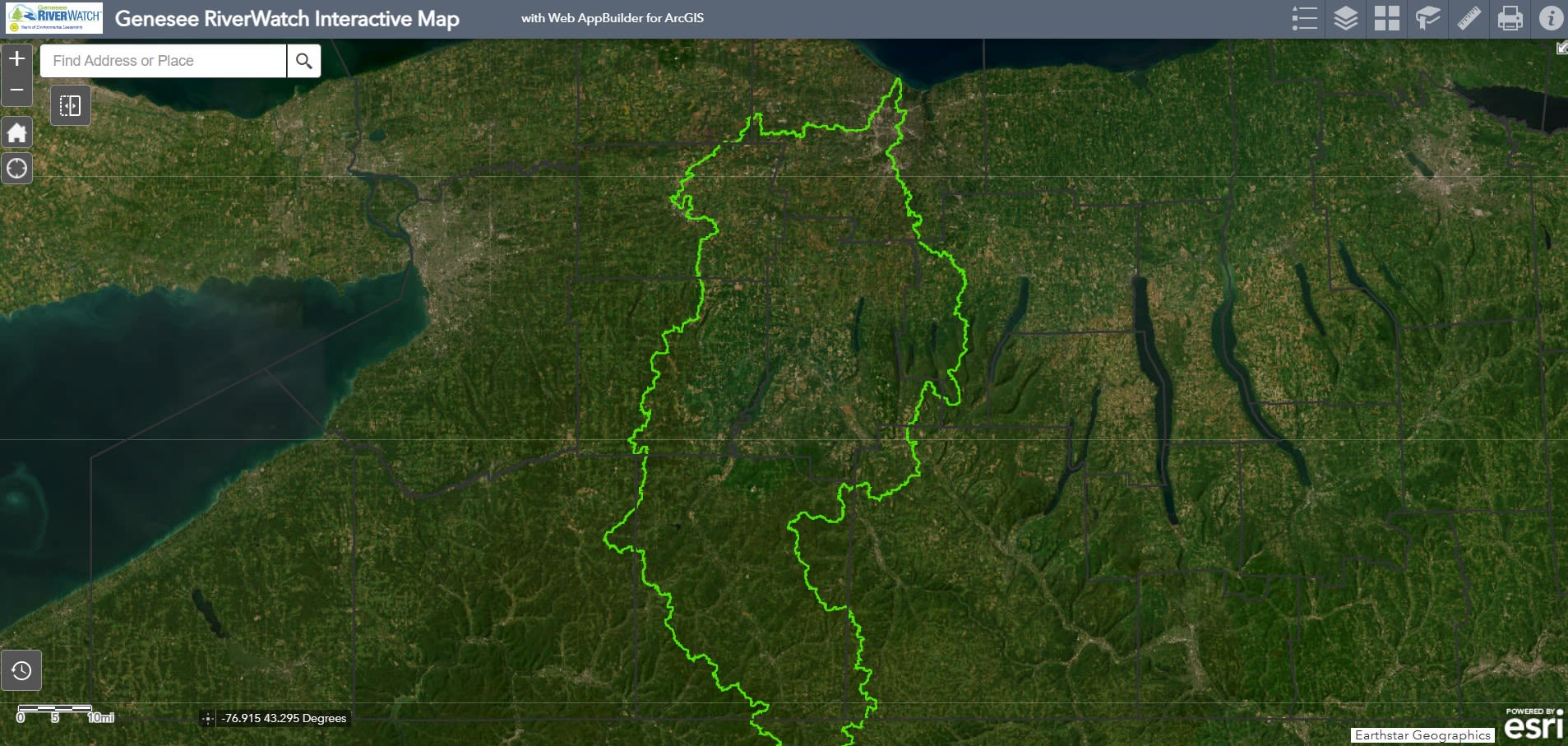

Genesee River Basin/Watershed Outline

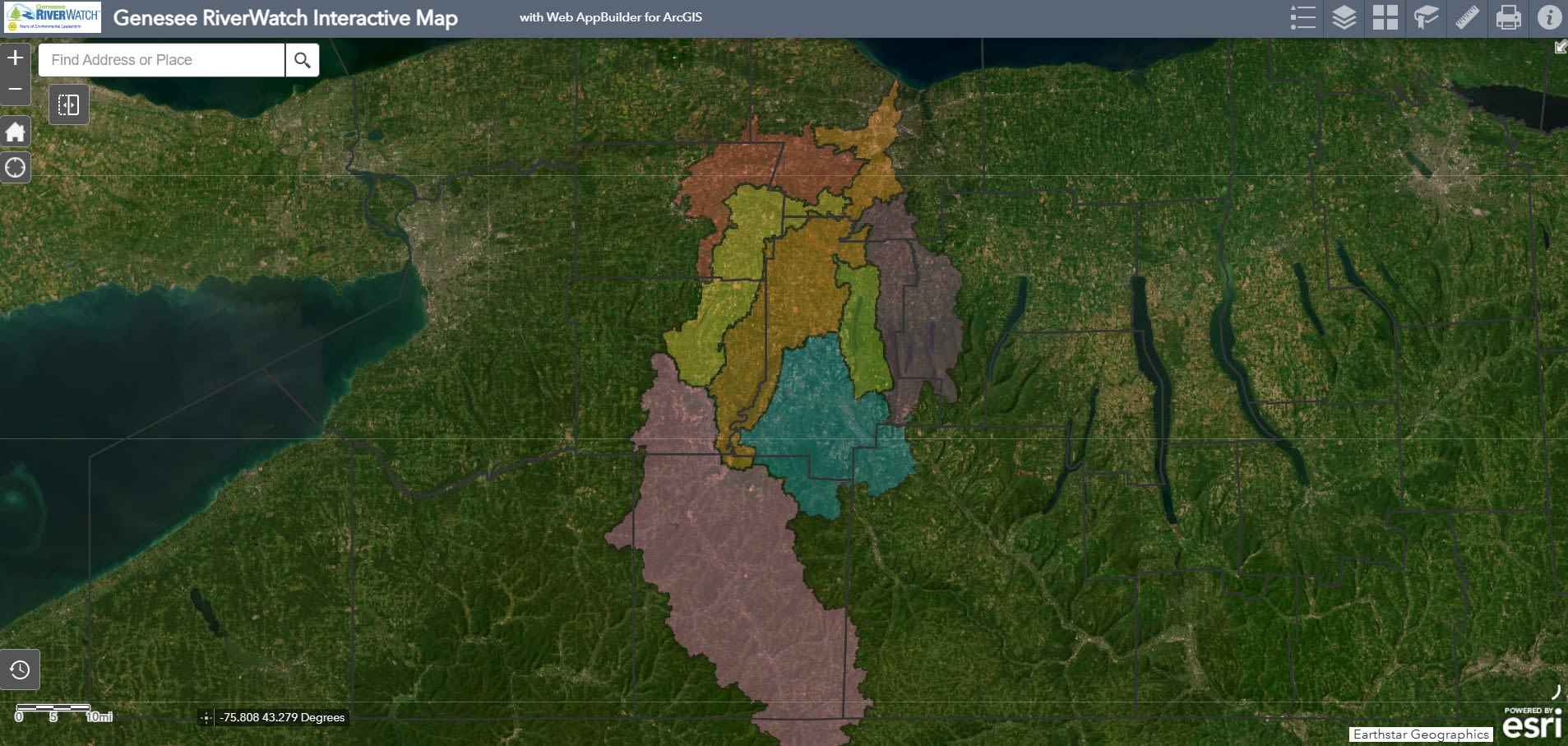

Genesee River Basin/ Watershed with subwatersheds

Genesee River Basin/Watershed with counties

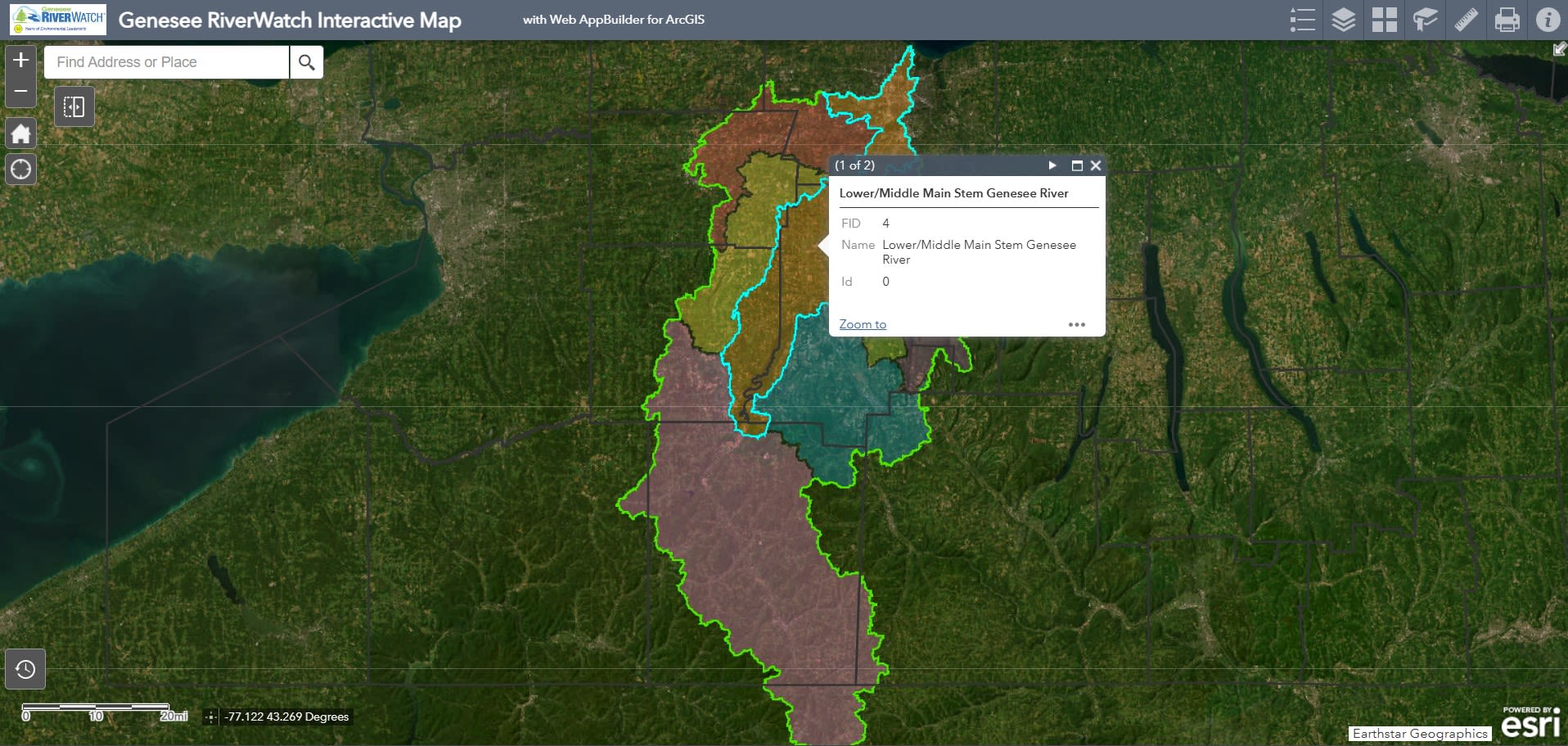

Subwatershed for Rochester: Lower/Middle Main Stem

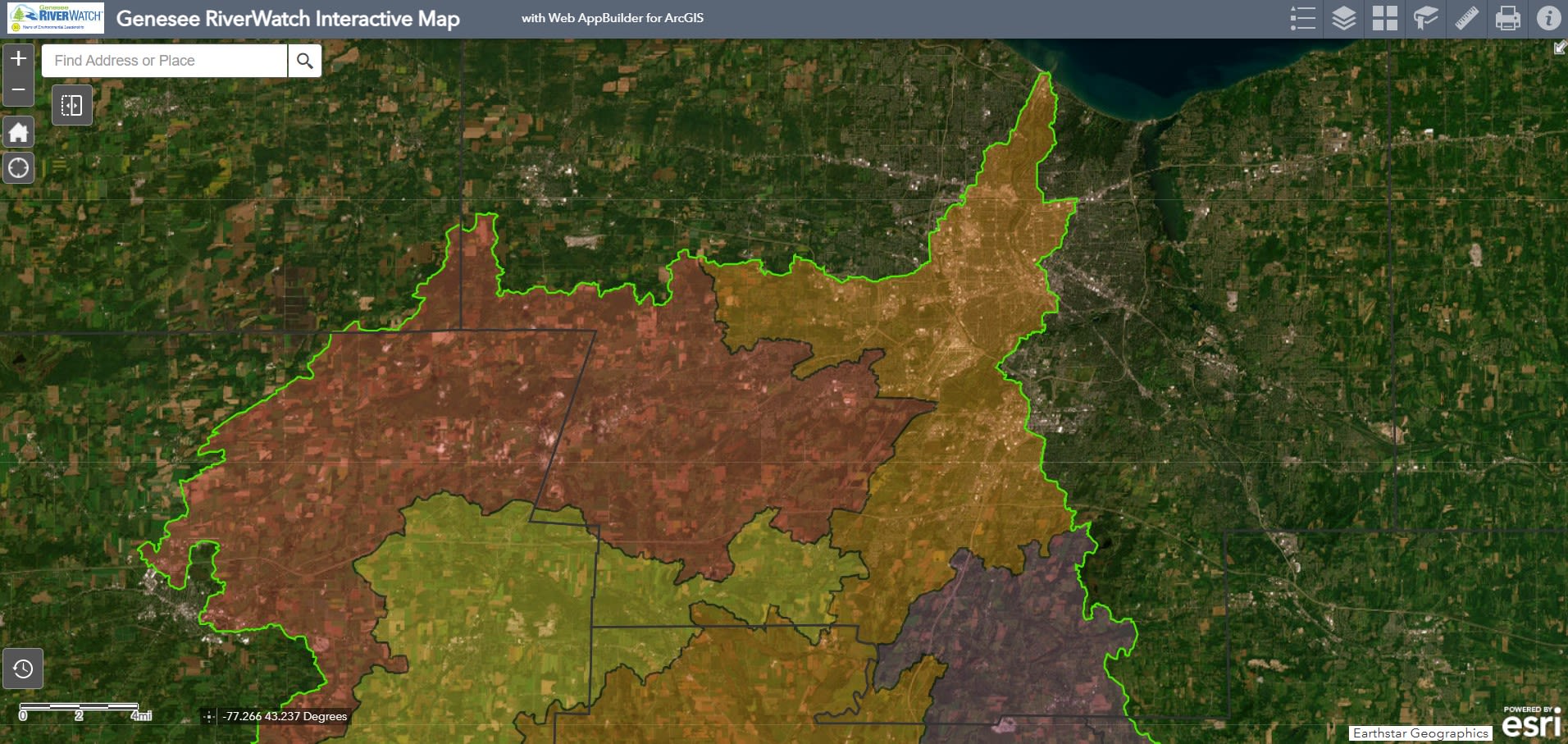

Close up of Lower/Middle Stem Subwatershed

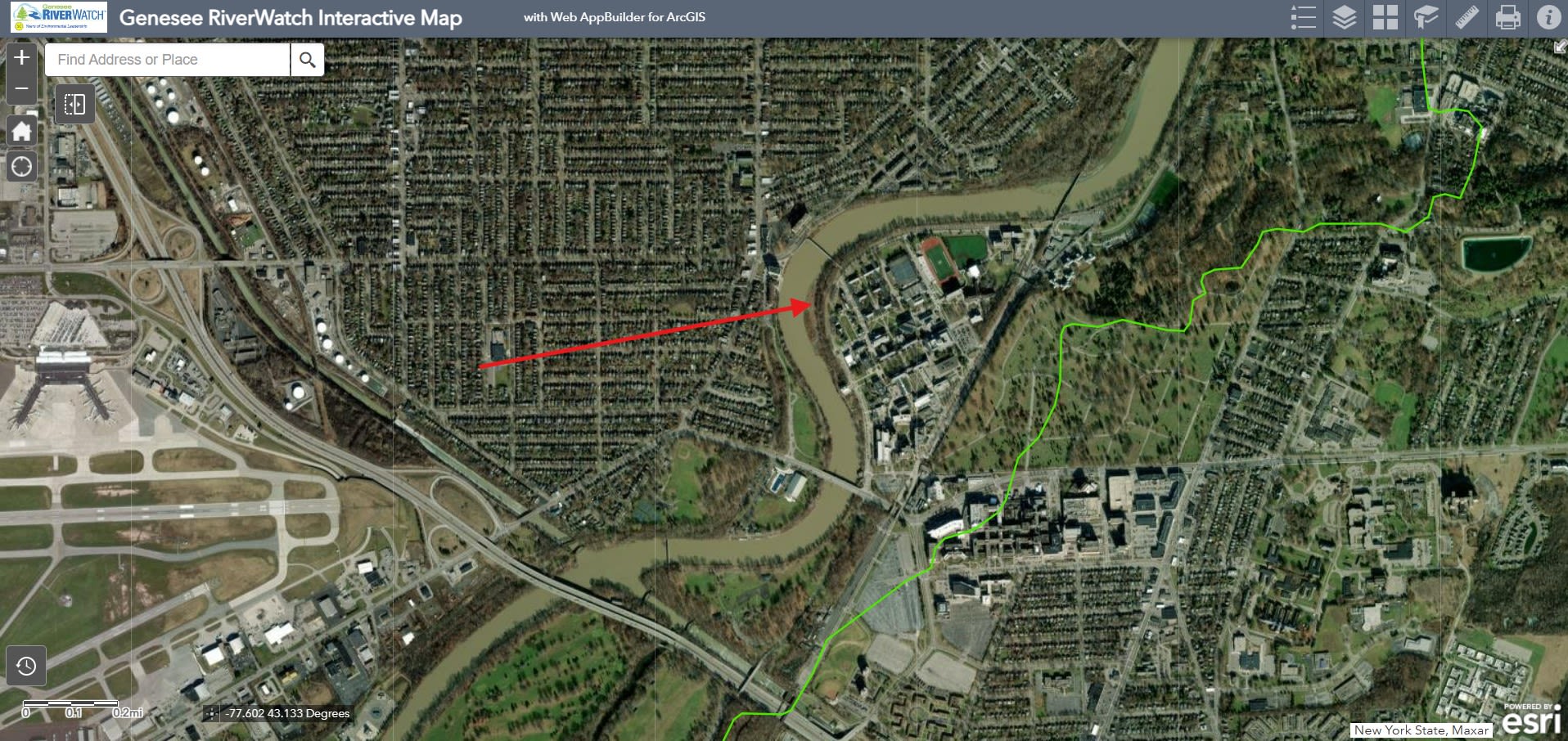

University of Rochester on Genesee River in the Lower/Middle Stem Subwatershed

The Ahná:wate/ Raquette River

Highway of the Adironadacks

Ahná:wate" is the Kanien'kehá (Mohawk) name for the Raquette River, There are different stories about how the river gained “Raquette” as a moniker.

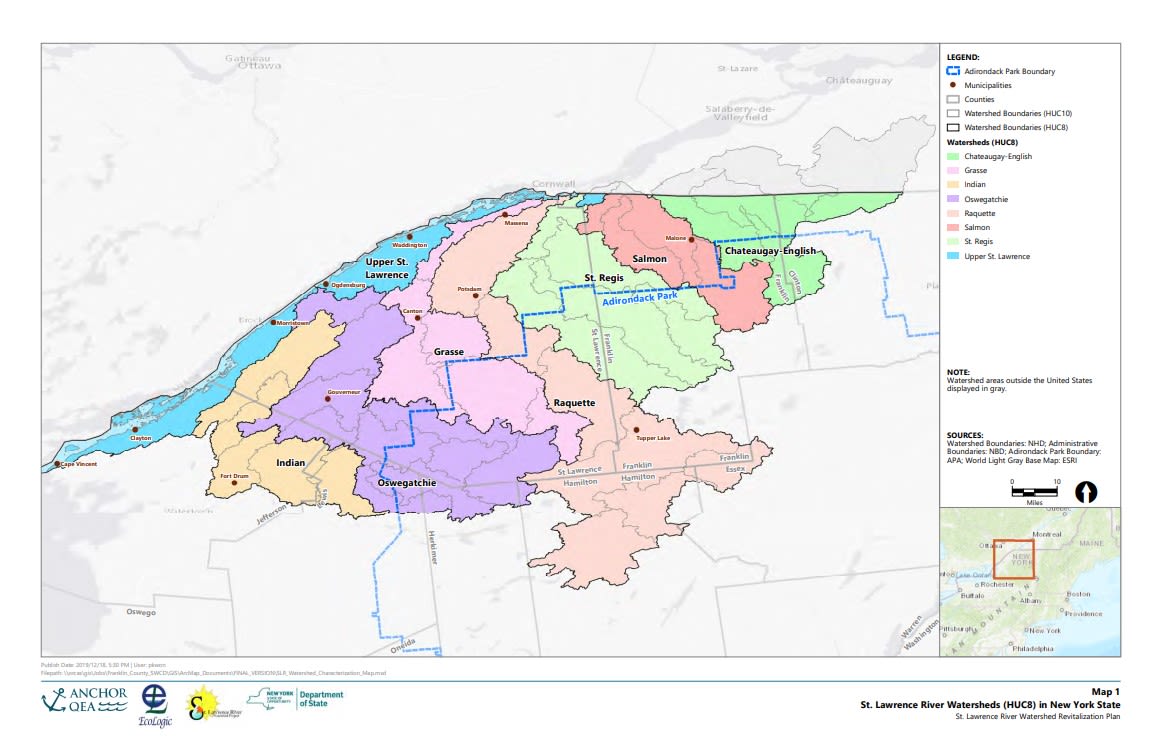

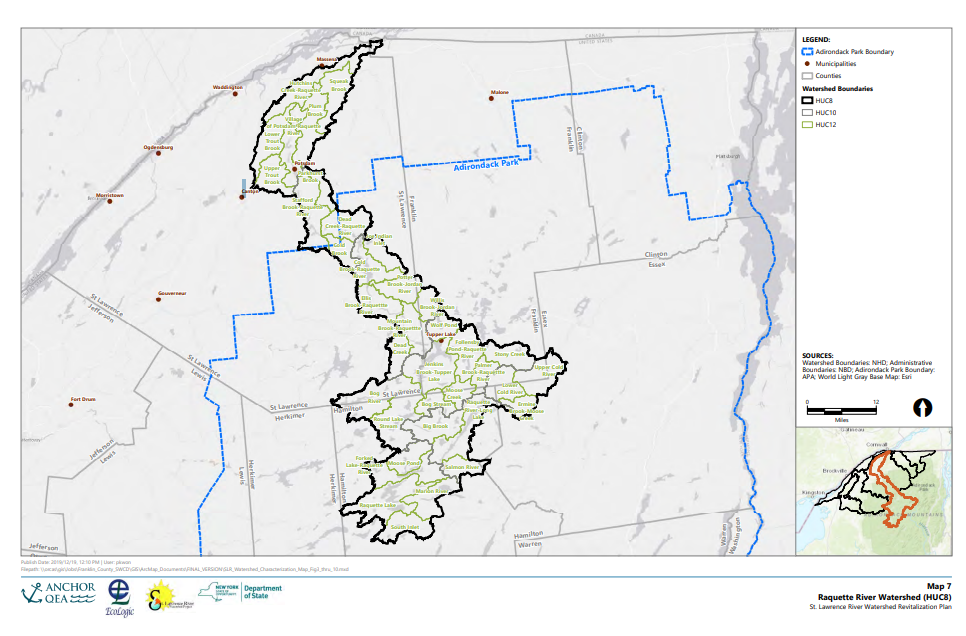

The Raquette River originates in the Adirondack highlands at Raquette Lake, Blue Mountain Lake, and Long Lake. Located in the the St. Lawrence River Watershed, it flows through Hamilton, Franklin, and St. Lawrence counties. It runs in a northerly direction and empties into the St. Lawrence River near Akwesasne. As the second longest river in New York, the Raquette runs 146 miles in a northerly direction.

The history of human settlement on the banks of the Raquette spans at least 5,000 years. In 2014, the SUNY Potsdam Anthropology Department discovered prehistoric Native American artifacts in an organized dig. The Raquette River was historically used as the "Highway of the Adirondacks," a route for travel by canoe and guideboat, as well as portage trails connecting numerous waterways, all now part of the Northern Forest Canoe Trail.

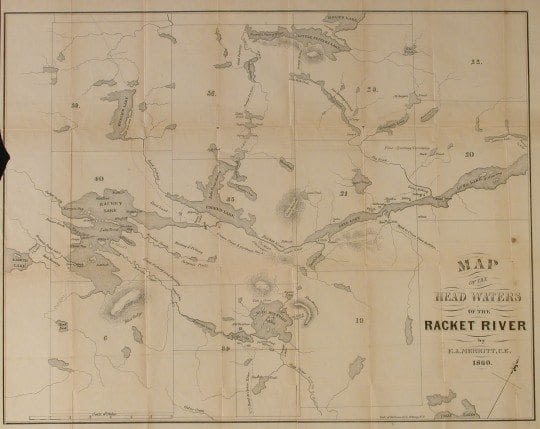

Map of Head Waters of the Racket River (sic). E.A. Merritt, 1860

Map of Head Waters of the Racket River (sic). E.A. Merritt, 1860

The "Highway of the Adirondacks" was also used for log drives to transport timber to mills. The logging industry in the 1850s set the stage for the construction of dams along the Raquette, many of which are now used for hydroelectric power. The river is the source of 27 hydroelectric plants operated by Brookfield Power, which at capacity can produce up to 181 megawatts of power.

The Raquette River remains the "Highway of the Adirondacks," but with 80% of the shoreline now state land under conservation, the highway is one of canoeing, kayaking, and fishing. A web of portage trails connects ther Raquette with lakes and other local waterways.

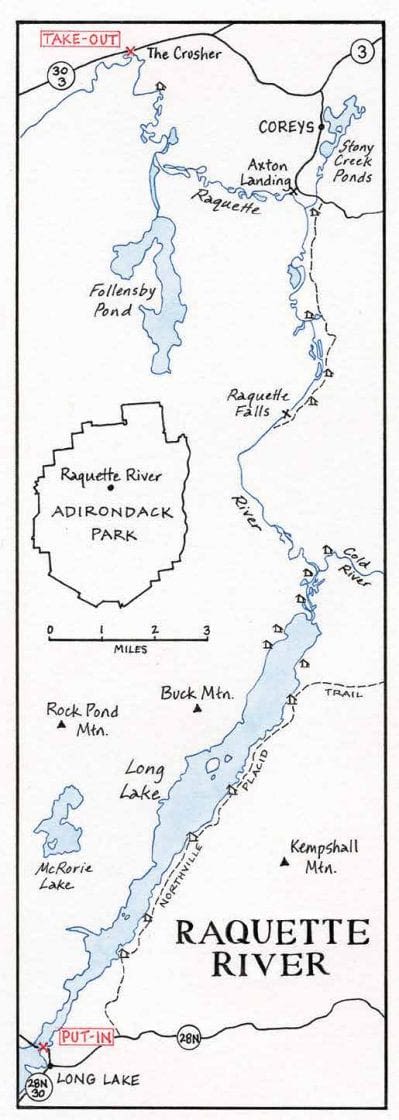

Portage Map of the Raquette River. Credit: Nancy Bernstein

Portage Map of the Raquette River. Credit: Nancy Bernstein

Challenges for the Raquette

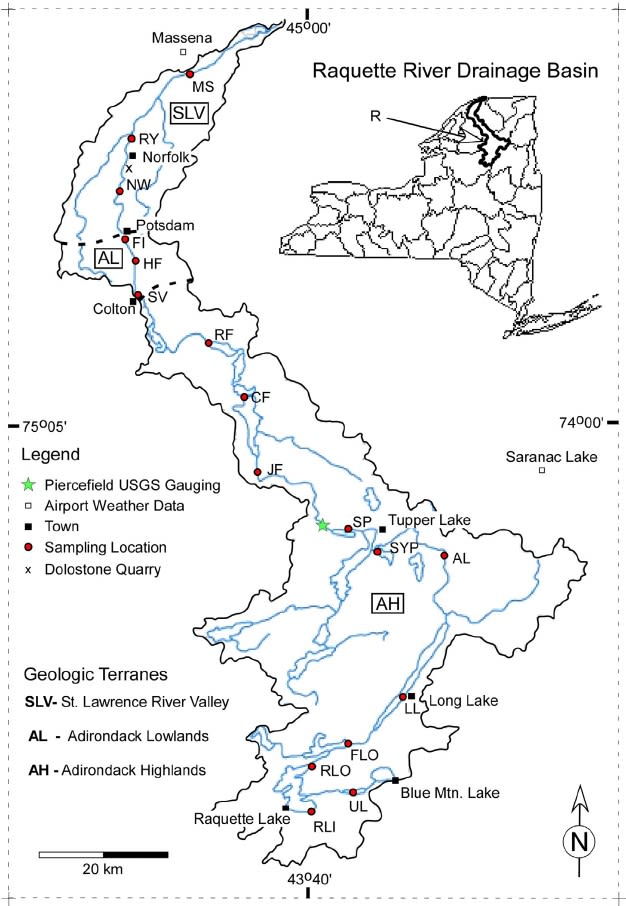

There are a number of challenges facing the Raquette River and its watershed, including fecal contamination, microplastics, road salt runoff, invasive species, and nutrient overload. The following findings are based on a series of sampling sites, as detailed in the map below.

Chiarenzelli and Skeels, Journal of Hydrology, 2014.

Chiarenzelli and Skeels, Journal of Hydrology, 2014.

Fecal Coliforms

Old and failing septic systems are the cause of elevated levels of fecal coliform bacteria in the Raquette, which can result in E. coli contamination and a number of illnesses. This adds to elevated phosphorus levels to trigger nutrient overload, which can lead to harmful algae blooms (HABs).

Microplastics

A recent NIH pilot study (Haque, Holson, and Baki) examined microplastics in water and sediment samples from the Raquette River and found that microplastic pollution is highest in a river confluence for water samples and downstream of a wastewater treatment plant for sediment samples. Microplastics in all their forms endanger the entire ecosystem of the watershed.

Road Salt Runoff

The St. Regis Mohawk Tribe, along with other organizations, has actively led the charge to reduce the use of road salt in the Adirondacks. The Adirondack Council published Low Sodium Diet in 2009, "an analysis of winter road maintenance practices, negative impacts of salt pollution, and recommendations for road salt reduction and alternatives."

Additional Challenges

The Raquette faces additional challenges that are being managed and mitigated in various ways. These challenges include, but are not limited to:

- Harmful algal blooms (HABs), caused largely by nutrient overload induced by elevated levels of phosphorus

- Invasive species which can negatively impact native ecosystems, water quality, and human recreation. The Adirondack Council, in concert with NYSDEC and other organizations, is working to prevent the spread of invasive species into the many waterways of the Adirondacks.

- Effects of dams on the river, some of which cause significant negative environmental impacts, such as habitat destruction, alterations to natural river flow, changes in water quality and temperature, and disrupting fish passage throughout the waterways.

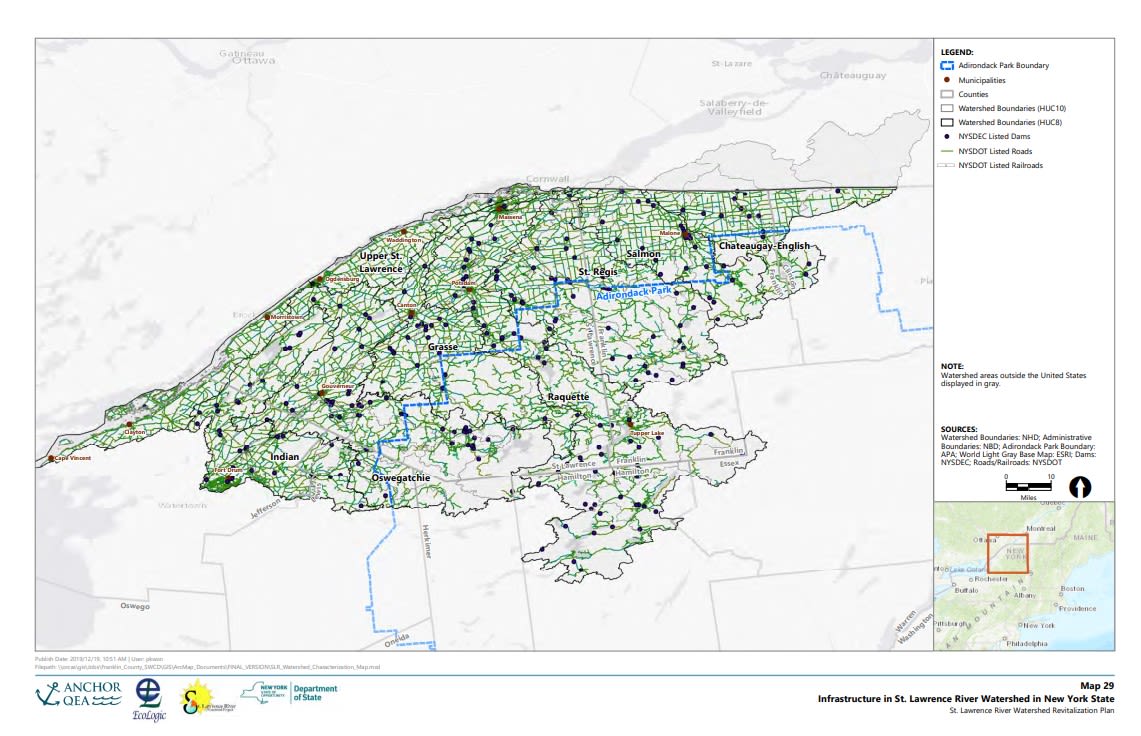

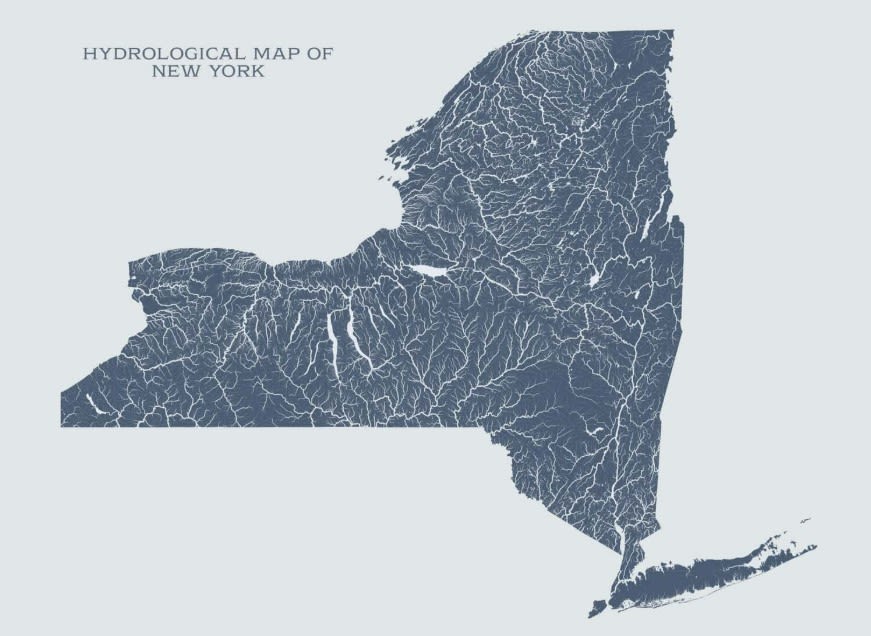

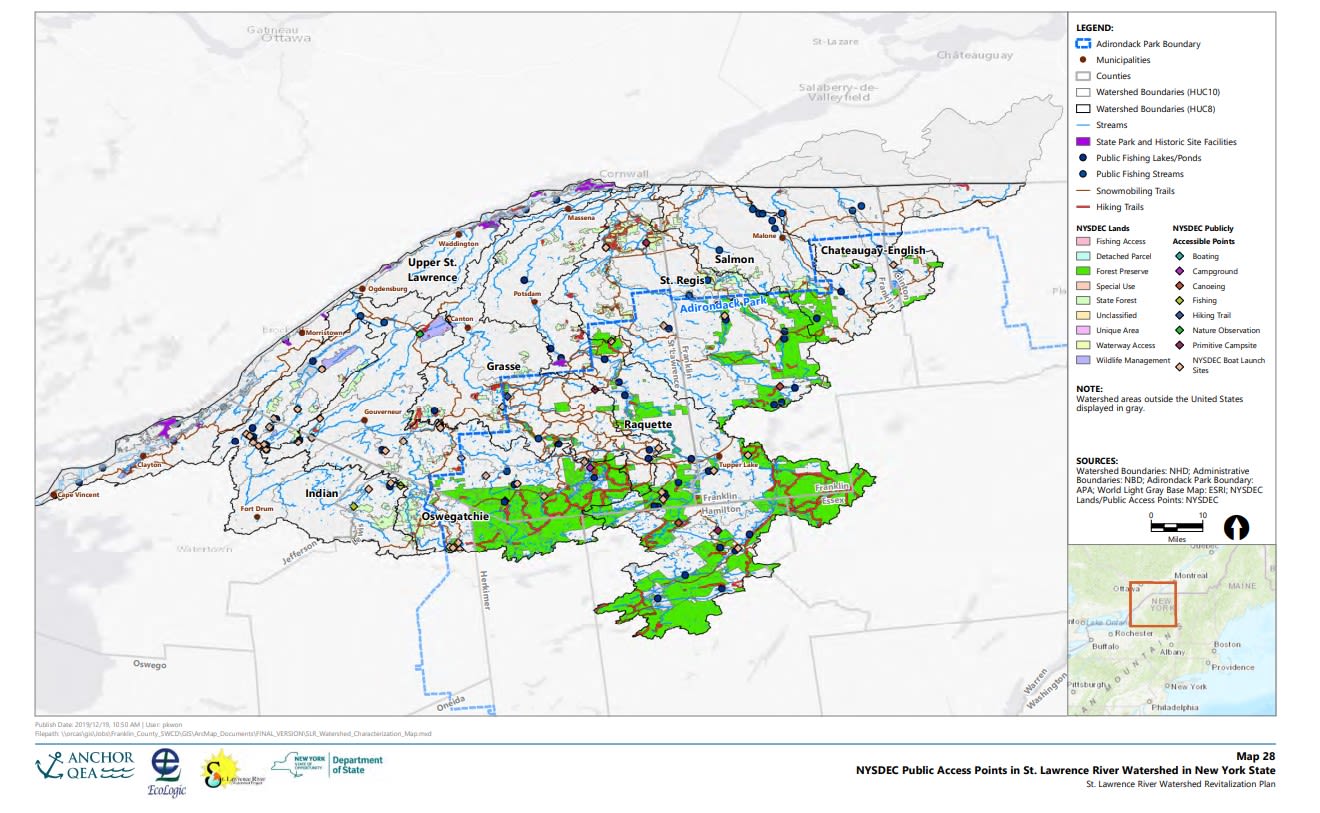

Hydrological Map of New York

St. Lawrence Watershed Sub Basins

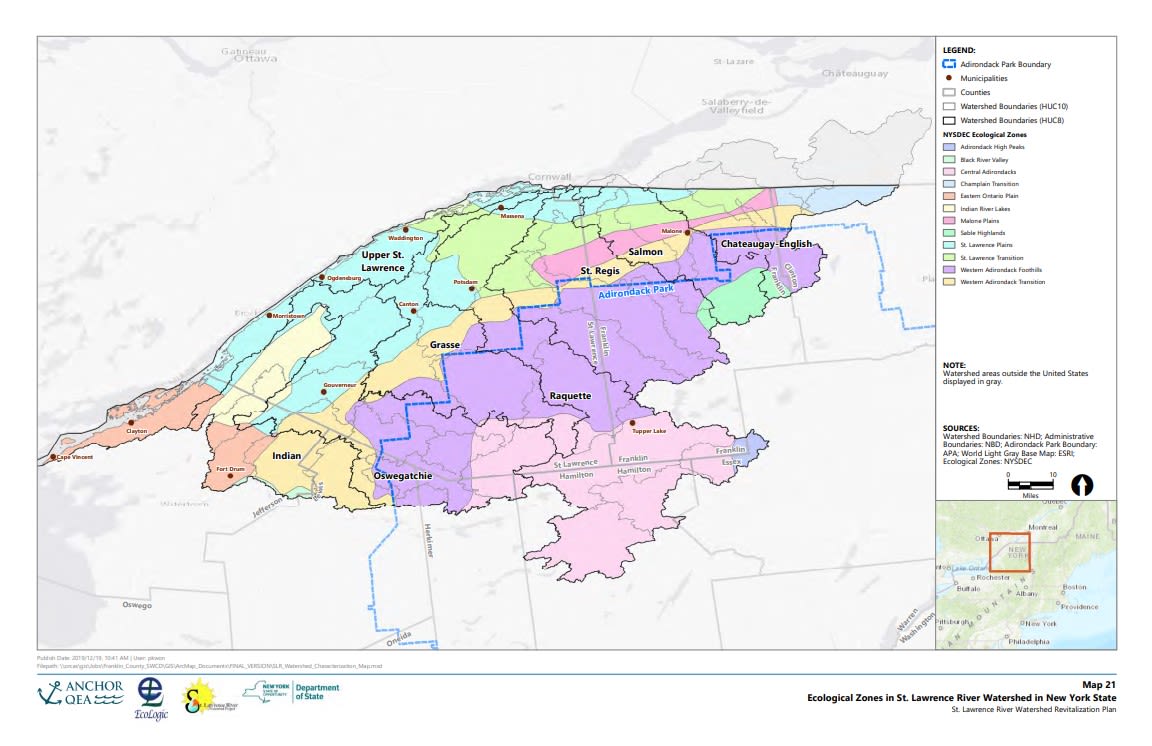

Ecological Zones

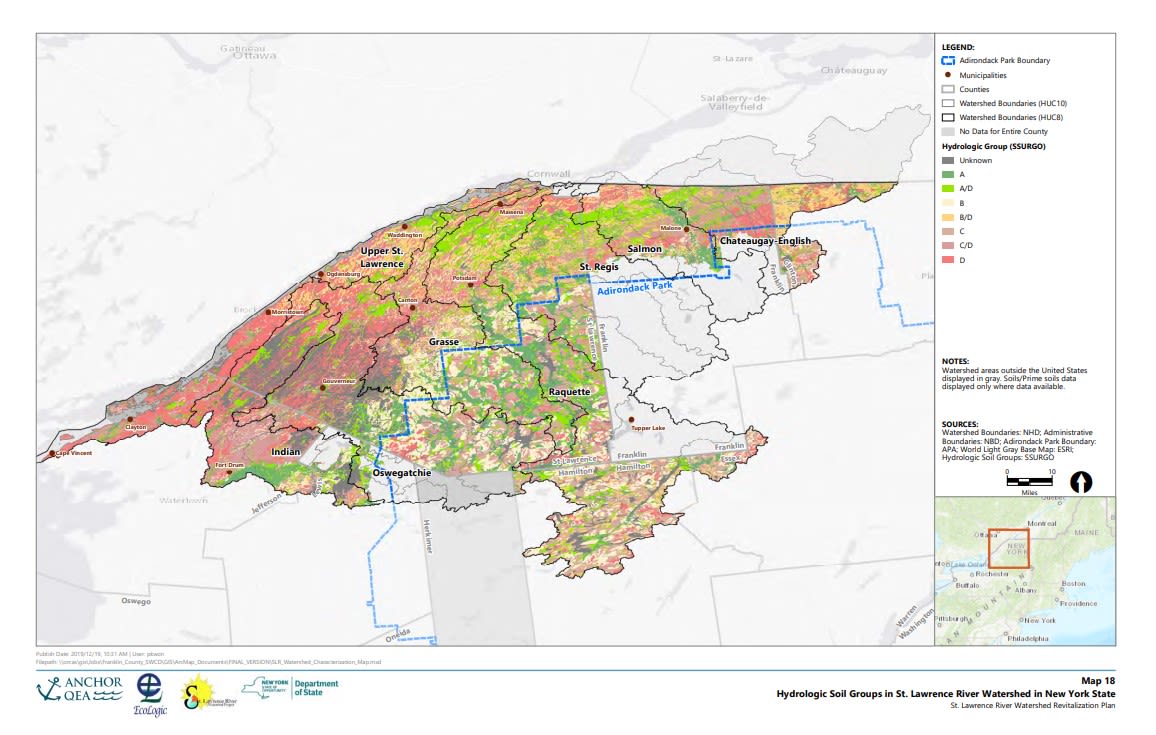

Hydrologic Soil Groups

Public Access Points

Raquette River Sub Basin

Resources

What can I do? What can we do?

- Know where your water comes from.

- Reduce or eliminate fertilizer and pesticide use.

- Reduce polluted runoff.

- Use biodegradable cleaning products and dispose of non-biodegradable products properly.

- Help with river clean-up events.

- Advocate for healthy water policy.

- Listen to Indigenous groups and learn from traditional ecological knowledge.

- Work on restoration and stewardship projects in the community.

- Join local groups to become a Waterkeeper or River Guardian.

- Get to know your river.

- Tell your water story!

Research and support these groups for the Genesee!

- Genesee River Watch

- Genesee River Alliance

- Rochester Ecology Partners

- Genesee River Watershed Coalition

- Lower Falls Foundation

- Stormwater Coalition of Monroe County

- Greentopia

- ROC the Riverway

- Waterkeeper Alliance

Research and support these groups for the Raquette!

- Adirondack Almanack

- The Adirondack Common Ground Alliance

- The Adirondack Council

- Adirondack Research Consortium

- Adirondack Watershed Institute (Paul Smith's College)

- The Nature Conservancy

- New York State Department of Environmental Conservation

- North Country Public Radio

- Northern Forest Canoe Trail

- The Wild Center

- Talking Rivers

- Waterkeeper Alliance

What's your water story?

Water Stories: Narrative and Science

"Water needs many biographers."

Water stories help us to understand our waterways, each other, our communities, and ourselves. Water stories also serve as an archive for community experience as well as provide data points for research on waterways over time to determine the effects of climate change, urbanization, and other anthropogenic trends.

An inherent part of the Watershed Movements Project is collecting community stories about specific rivers and general waterway experiences. These stories will be digitally mapped to the locations where they were collected, creating an interactive audio map that is accessible to the broader community.

Story Doula Almeta Whitis offers waters stories based on Conduits of Time and Legacy.

Aerial view of Irondequoit Creek, Rochester, NY (A. Gluckman)

Aerial view of Irondequoit Creek, Rochester, NY (A. Gluckman)

Aerial view of Lake Ontario, Oswego, NY. (A. Gluckman)

Aerial view of Lake Ontario, Oswego, NY. (A. Gluckman)

Blue Hole, Phillips County, AR. (A. Gluckman)

Blue Hole, Phillips County, AR. (A. Gluckman)

Aerial view of the Mississippi River, Helena, AR. (A. Gluckman)

Aerial view of the Mississippi River, Helena, AR. (A. Gluckman)

Bank of the Mississippi River, AR. (A. Gluckman)

Bank of the Mississippi River, AR. (A. Gluckman)

Mississippi River, Phillips County, AR. (A. Gluckman)

Mississippi River, Phillips County, AR. (A. Gluckman)

Aerial view of Rice Creek, Oswego, NY. (A. Gluckman)

Aerial view of Rice Creek, Oswego, NY. (A. Gluckman)

Aerial view of Irondquoit Creek, Rochester, NY. (A. Gluckman)

Aerial view of Irondquoit Creek, Rochester, NY. (A. Gluckman)

Full moon over the Mississippi River (A. Gluckman)

Full moon over the Mississippi River (A. Gluckman)

Tupper Lake, NY. (A. Gluckman)

Tupper Lake, NY. (A. Gluckman)

"Still the rivers prevail. They will outlast us all. But we will not endure without them." -- Laurence Smith