These Walls Can Talk

What One Building Can Teach America

This project has been funded by the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Telling the Full History Preservation Fund, with support from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this exhibition do not necessarily represent those of the National Trust or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

These Walls Can Talk is a project of the Elaine Legacy Center, parent to the Elaine Museum and Richard Wright Civil Rights Center. Standing at the crossroads of Highways 85 and 44 in Phillips County, Arkansas, is a building that has witnessed the turbulent forces of American history--devastating floods, incomprehensible racial violence, and persistent poverty. However, this same building has witnessed black settlement and prosperity, immigrant integration, and a rich history of multiple cultures and stories. The project tells the history of a small delta town in Arkansas that has witnessed the fullness of American history, both tragedies and triumphs, through the experiences of its oldest known building, 100 Main Street in downtown Elaine, Arkansas. What can this building teach America about itself?

Preserving original bricks of 100 Main Street. (Photo credit: Andrea Gluckman)

Preserving original bricks of 100 Main Street. (Photo credit: Andrea Gluckman)

THESE WALLS CAN TALK

If these walls could talk, what would they say? The walls of 100 Main Street in Elaine, Arkansas can talk.

They talk today through the oral stories of people who walk by and walk in. What began as an outpost in a rural village became a drug store, a post office, a grocery store, and now--the repository of memory of over 100 years of American history. At the crossroads of history, the walls of 100 Main Street narrate the stories of this project, the stories of the people of Elaine, Arkansas.

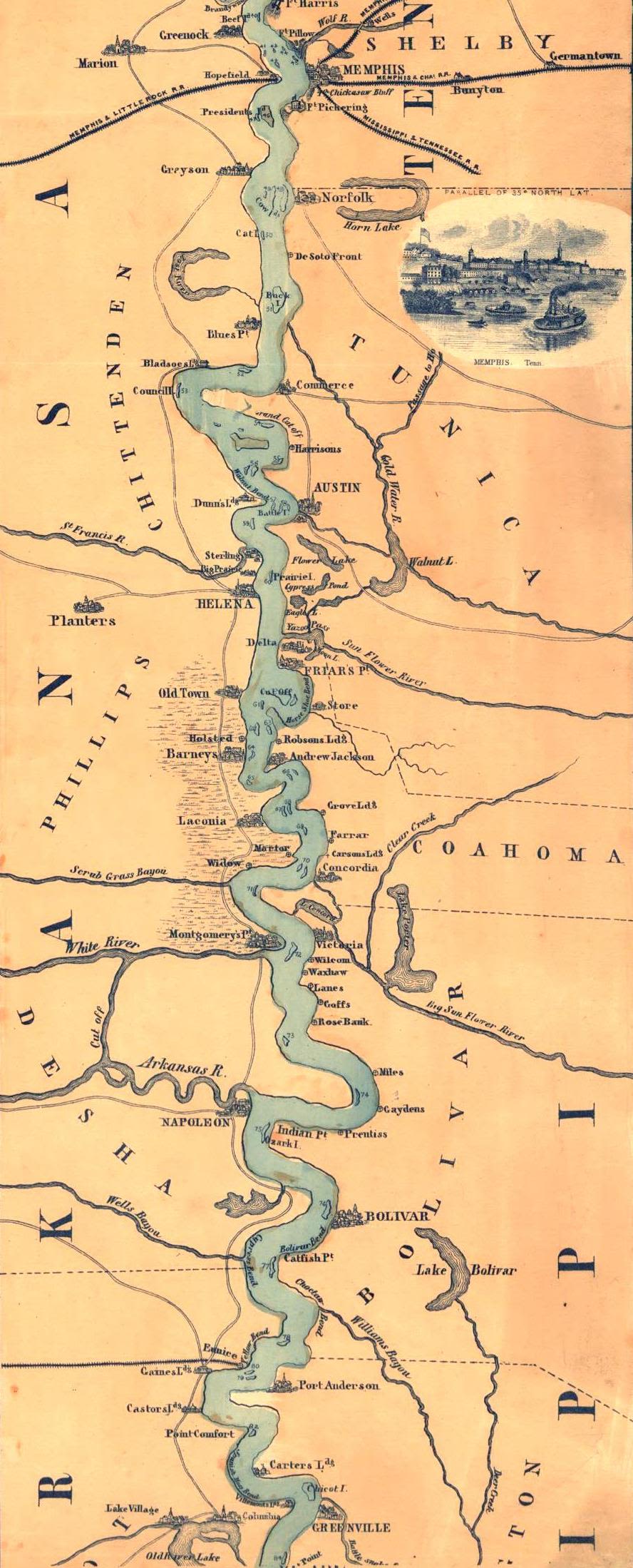

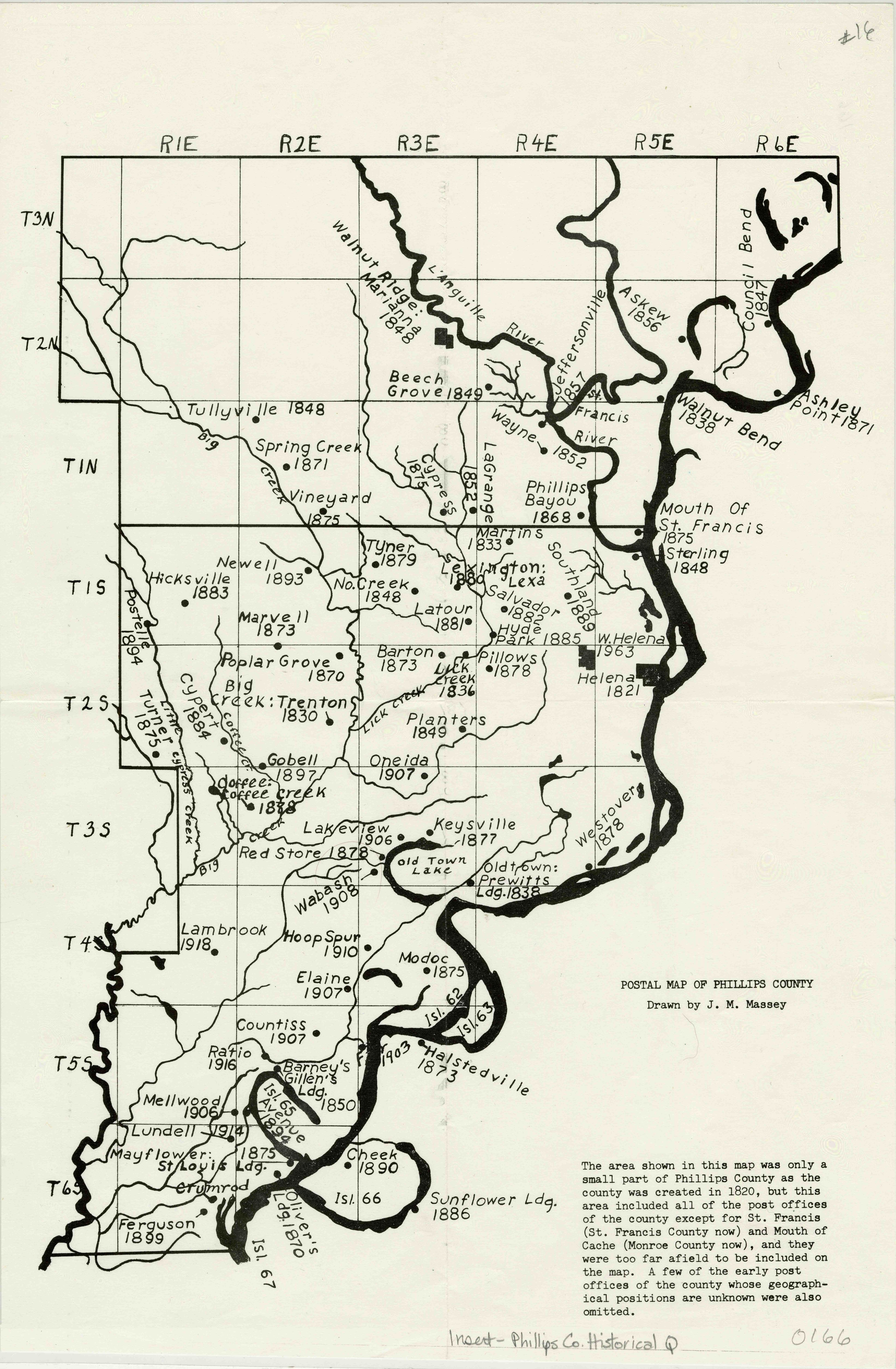

Elaine is located in southern Phillips County, Arkansas, embedded in the alluvial plain between the Mississippi and White Rivers. The second oldest county in Arkansas, Phillips County has a long cultural history of indigenous habitation, colonization by European settlers, enslavement of African Americans, and a complex experience of the Civil War and Reconstruction. Agriculture and timber have dominated the economic development of the county, aided by the ample waterways and railroads.

Panorama of the Mississippi Valley and its fortifications by F.W. Boell. Shows towns, railroads, river landings, some plantations, 1836. Library of Congress.

Panorama of the Mississippi Valley and its fortifications by F.W. Boell. Shows towns, railroads, river landings, some plantations, 1836. Library of Congress.

Postal map of Phillips County, drawn by J.M. Massey. (Source: Tri-County Geneaological Society)

Postal map of Phillips County, drawn by J.M. Massey. (Source: Tri-County Geneaological Society)

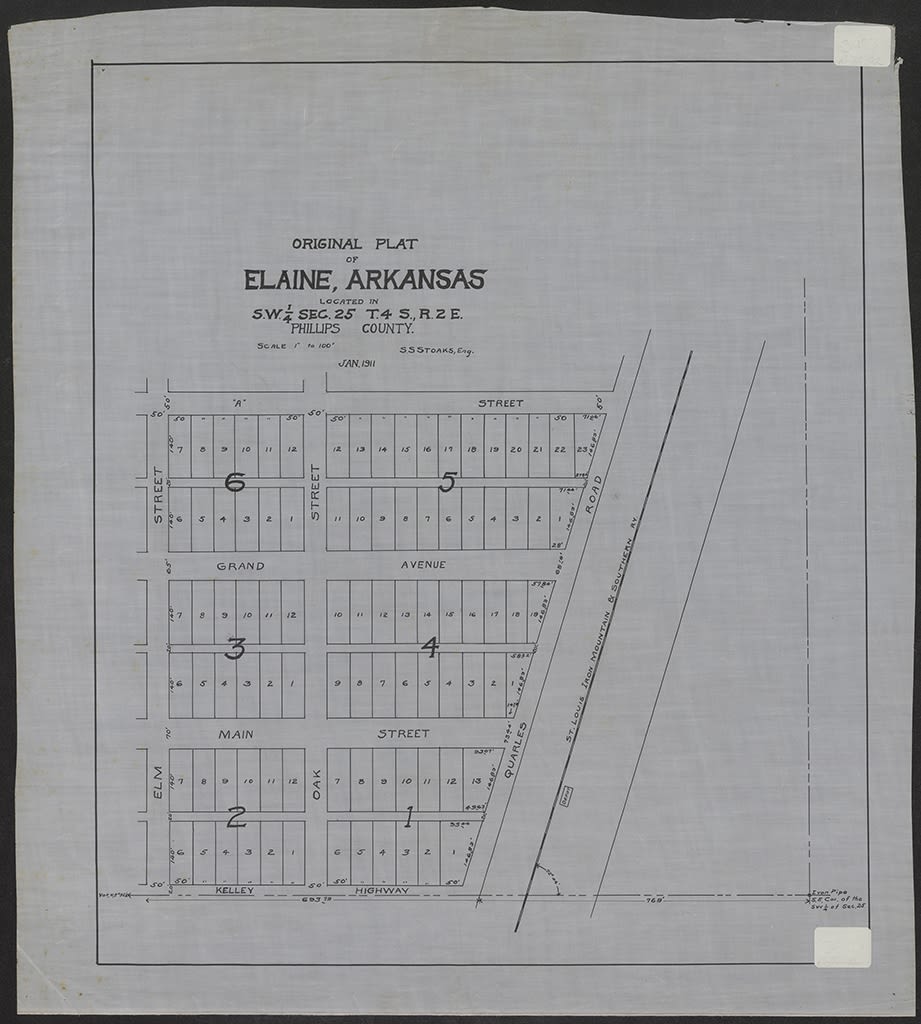

Original Plat of Elaine, AR. January 1911 (Source: UALR Maps M-073, UA Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture)

Original Plat of Elaine, AR. January 1911 (Source: UALR Maps M-073, UA Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture)

The history of 100 Main Street in Elaine can be laid out in four time periods--beginning with construction in 1915 through to the present-day restoration--told through oral histories, maps, documents, and community stories. This project is a testament to those walls.

The northern back wall of the inside of the museum with scaffolding. (Photo credit: Andrea Gluckman)

The northern back wall of the inside of the museum with scaffolding. (Photo credit: Andrea Gluckman)

These Walls Can Talk is based on the following premises:

Truth comes from the oral stories of those who live through tragedies and triumphs in the midst of oppression.

Official narratives of historical events often tell another story.

Truth builds a foundation of historical justice to lead the struggles for justice today.

Microcosms of historical accuracy, like Elaine, together comprise the history of a nation born in inequity, struggling to find life, liberty, and justice for all.

“When people take you to historic places, if they don’t take you to Elaine, they have not taken you to enough places.”

These Walls Can Talk is a community-built project based on oral histories, photographs, documents, videos, podcasts, and tireless research. The outcome is a snapshot of American history from a small southern town, as told through the experience of one building. The walls of 100 Main Street have survived much since their construction in 1915 and today stand as a testament to the resilience of the people of the Arkansas delta.

“We used the Bible and the Constitution. And we freed ourselves. Our history is unparalleled."

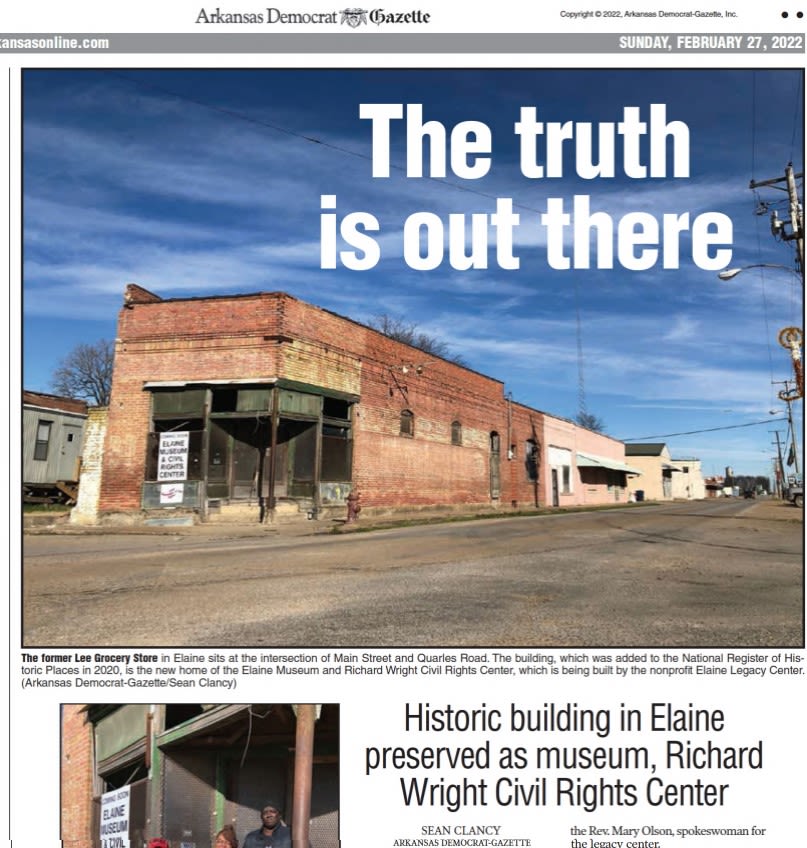

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette article by Sean Clancy, Feb. 27, 2022

Arkansas Democrat-Gazette article by Sean Clancy, Feb. 27, 2022

“We can learn so much by listening to descendants, to descendants of survivors, but also to people who live in Elaine and justice-seekers in general. Listen to their stories, listen to their memories, listen to the traditions that were passed down through the generations.”

Over 100 Years of History for 100 Main Street

1) Richard Wright's Elaine: 1915-1919

The first time period of the building's history covers its construction in 1915 and the period before, during which novelist Richard Wright lived in Elaine.

2) Massacre, Floods, and Cotton: 1919-1947

The second time period begins with the Elaine Massacre of 1919, moves through two major floods, and the rise of the cotton empires through the end of WWII.

3) Lee Grocery: 1947-2014

The third time period covers from the end of WWII through the era of Jim Crow to the 2000s. This era witnesses the arrival and integration of Chinese families into Phillips County. The Lee family owns and operates the building during this period as a grocery store.

4) Decline and Rebirth: 2014-present

After the building's time as a grocery store, it sits vacant for years until it is purchased to be repurposed into the Elaine Museum and Richard Wright Civil Rights Center.

1915-1919: A Time of Plenty

The building at 100 Main Street in Elaine was constructed circa 1915. A standard commercial twentieth-century-style building made of bricks and a simple floor plan, this building at the crossroads of Elaine stood witness to all that would come. As a consistent fixture of downtown Elaine, the walls of 100 Main Street saw the best and worst of the American experience. The first maps and pictures with 100 Main Street depict the building as a drug store. The building would also house the post office for a period of time.

The earliest known picture of 100 Main Street, seen on the left hand side of the photo in front of the train tracks. (Photo source: Phillips County History in Photographs)

The earliest known picture of 100 Main Street, seen on the left hand side of the photo in front of the train tracks. (Photo source: Phillips County History in Photographs)

The earliest known use for 100 Main Street was as a drug store, seen here on the corner. Photo courtesy of: Helena Museum

The earliest known use for 100 Main Street was as a drug store, seen here on the corner. Photo courtesy of: Helena Museum

"The truth is, if you look at the late 19th-century Delta, the majority of landowners in the Delta were African American. The Delta was the last standing hardwood forest in North America, and lumber companies came in there in the late 19th century after the Civil War and cleared these lands, and black people from the Eastern Seaboard migrated out to the Delta because they heard there were jobs, so they went out and they earned money—got to make wages—clearing the land. They took that money and bought land."

Dr. Nan Woodruff speaks about the causes of the Elaine Massacre of 1919 and how it fits into the post World War I context. (Source: Carnegie Council)

A man and woman pose on a Phillips County levee road. Undated photograph courtesy of: UALR Center for Arkansas History and Culture

A man and woman pose on a Phillips County levee road. Undated photograph courtesy of: UALR Center for Arkansas History and Culture

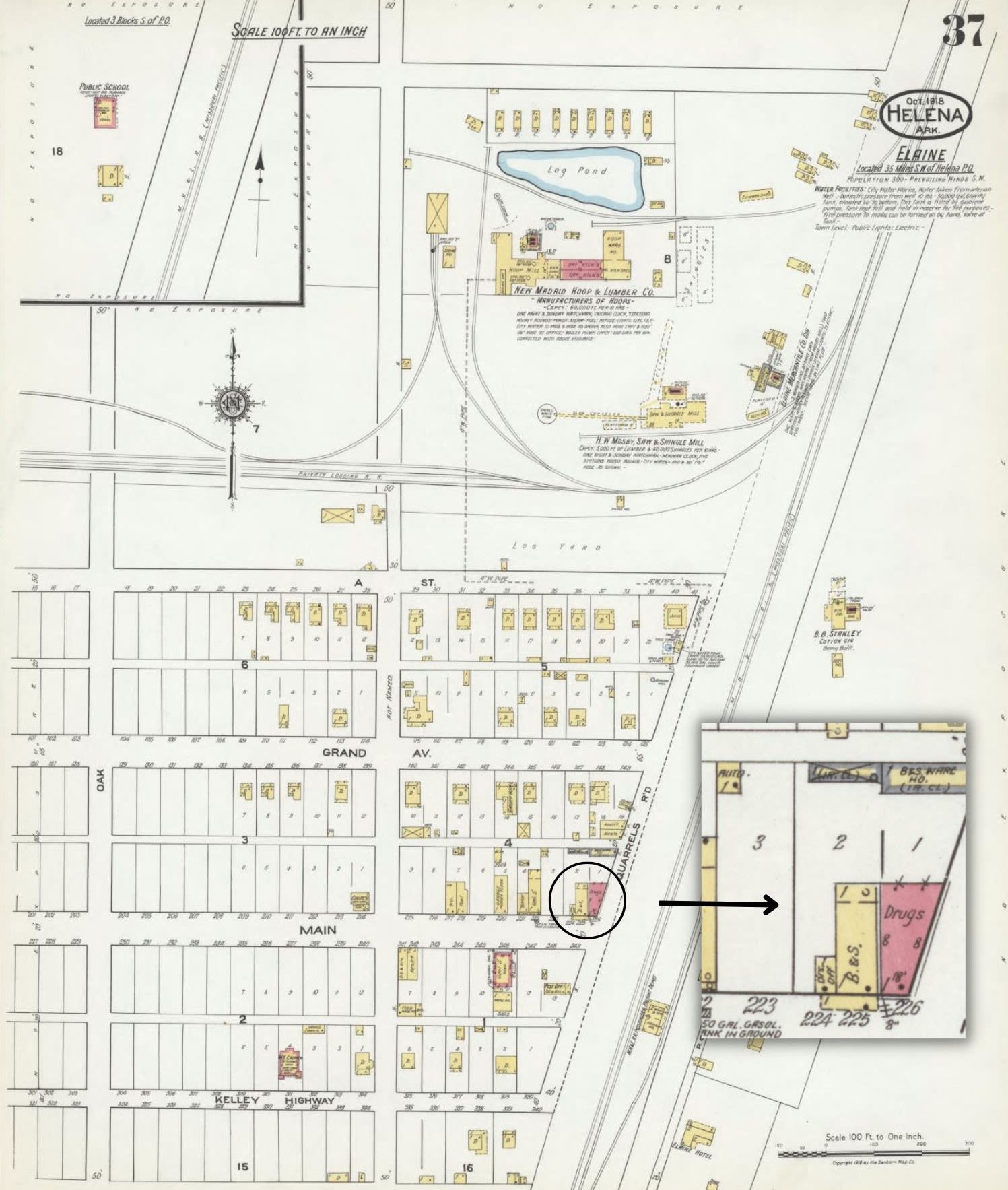

1918 Sanborn Map of Elaine, AR. Details reveals the first time 100 Main Street appeared on a map.

1918 Sanborn Map of Elaine, AR. Details reveals the first time 100 Main Street appeared on a map.

The building at 100 Main Street is located at the crossroads of downtown, Lot 1 on Block 4, as shown above in the map detail.

Researcher Jennifer Hadlock speaks about the earliest days of 100 Main Street and downtown Elaine.

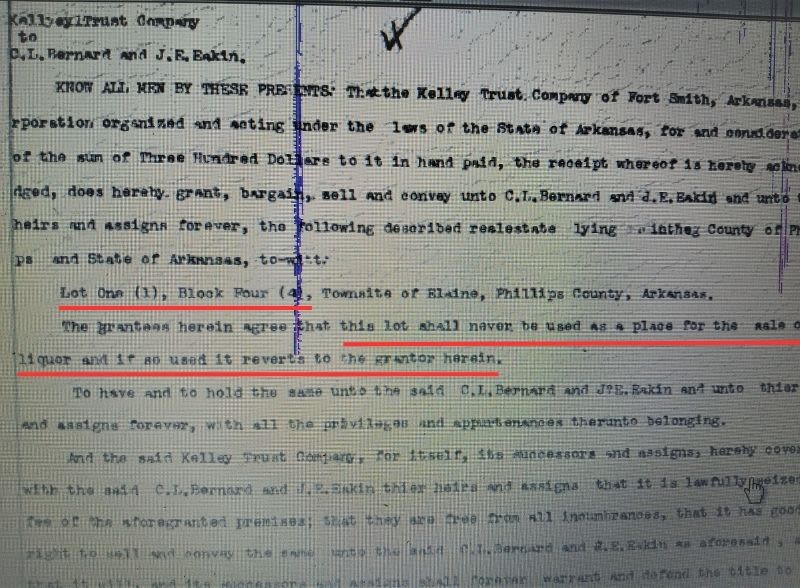

Land deed selling what is now 100 Main Street (Lot 1, Block 4) from the Kelley Trust to C.L. Bernard and J.E. Eakin, with an explicit clause that the sale of alcohol was forbidden.

Land deed selling what is now 100 Main Street (Lot 1, Block 4) from the Kelley Trust to C.L. Bernard and J.E. Eakin, with an explicit clause that the sale of alcohol was forbidden.

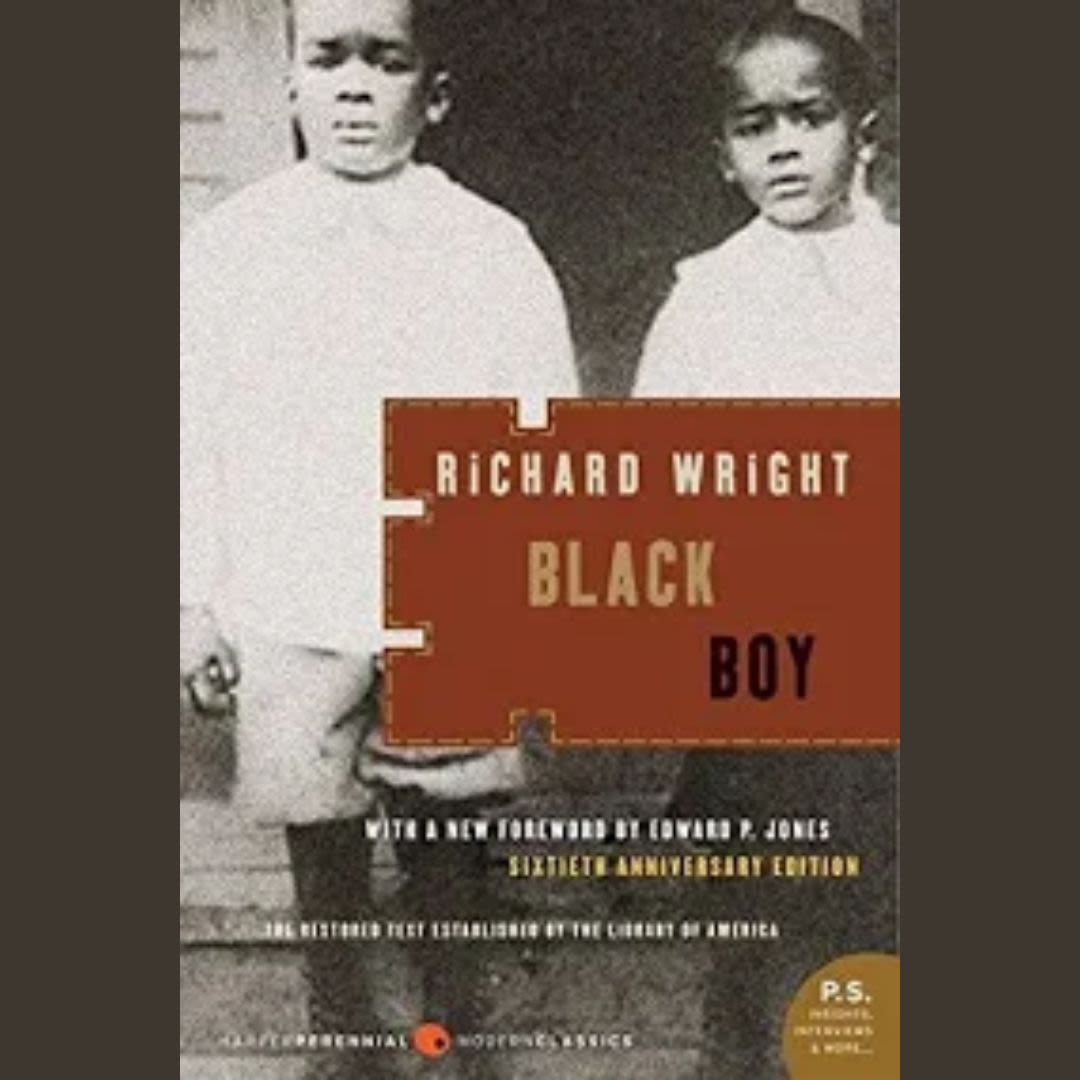

Richard Wright's Elaine

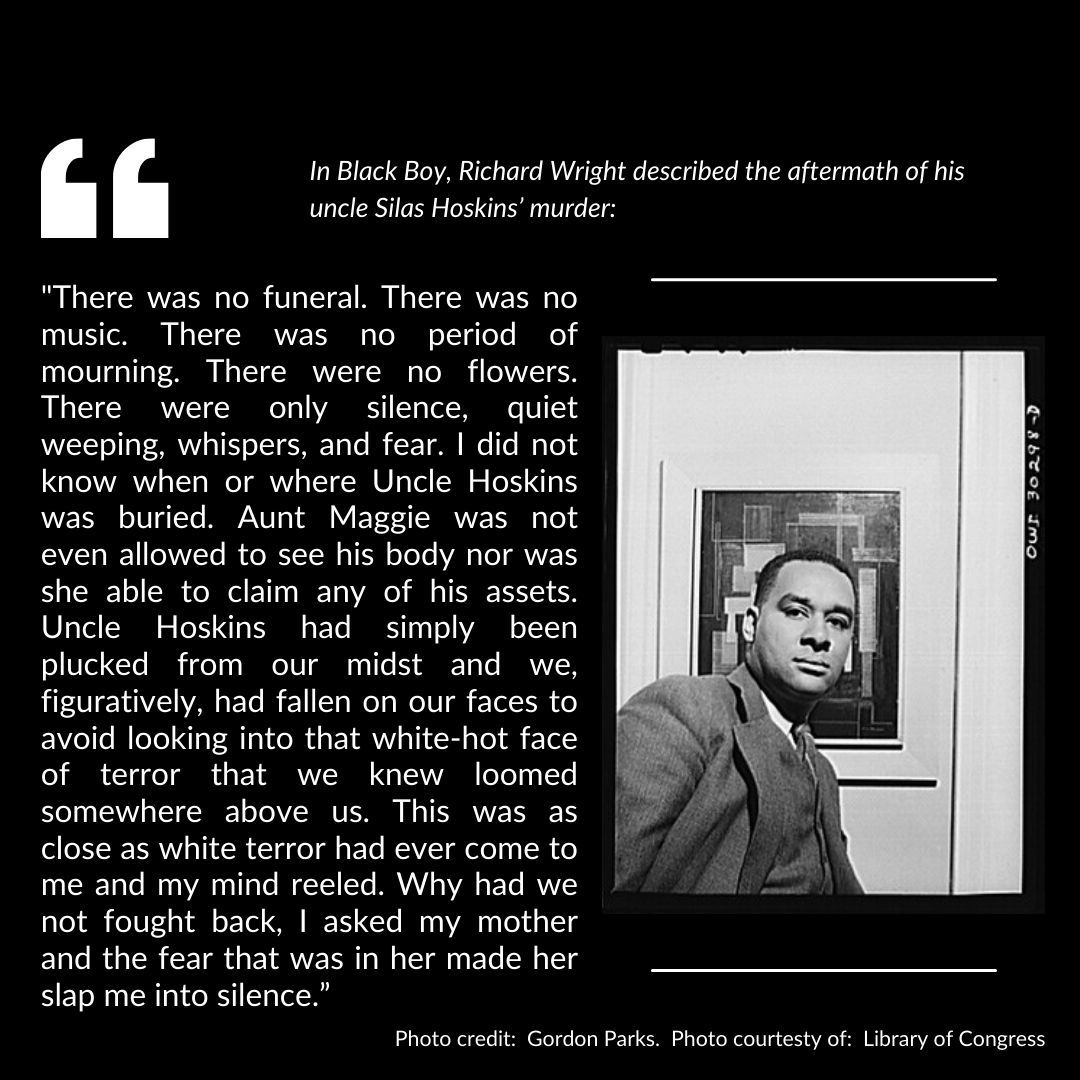

Novelist Richard Wright has a strong connection to Elaine, which can be discovered in Chapter Two of his memoir, Black Boy. Wright and his brother lived with his uncle Silas and aunt Maggie in Elaine before the Massacre of 1919. Richard most likely lived in Elaine when 100 Main Street was built.

Cover of Black Boy by Richard Wright

Cover of Black Boy by Richard Wright

The Wright family experienced Elaine as a welcome place of plenty, a place where Black people prospered and owned their own land and businesses. Among those prosperous people was Richard's uncle Silas Hoskins, a prominent business owner.

"When little Richard and little Leon, his brother, arrived in Elaine, it was like a fairy tale...For the first time, they were allowed to play...for the first time, they could eat to their hearts' content."

Through the research for this project, it has been discovered that the lot next door to 100 Main Street was home to the tavern owned by Uncle Silas. In 1916, Silas Hoskins was lynched, his body never returned to his family, his assets stolen, and his family traumatized. Richard and his family fled Elaine, but the connection has remained.

"I would like to thank Uncle Silas for what he did for us, for Elaine."

In the summer of 2022, the children of the descendants of the Elaine Massacre gathered soil in front of 100 Main Street for the National Memorial for Peace and Justice (informally known as the National Lynching Museum) in Montgomery, AL. The soil of Elaine will rest in honor to memorialize the Black victims of lynching through U.S. history. (Photo Credit: Andrea Gluckman)

In the summer of 2022, the children of the descendants of the Elaine Massacre gathered soil in front of 100 Main Street for the National Memorial for Peace and Justice (informally known as the National Lynching Museum) in Montgomery, AL. The soil of Elaine will rest in honor to memorialize the Black victims of lynching through U.S. history. (Photo Credit: Andrea Gluckman)

Julia Wright maintains her father's connection to Elaine through her work with the Elaine Legacy Center, her writing, and her tireless efforts for justice.

This area next to the museum (Lot 2) is believed to be the site where Silas Hoskins' tavern once stood. (Photo credit: Andrea Gluckman)

This area next to the museum (Lot 2) is believed to be the site where Silas Hoskins' tavern once stood. (Photo credit: Andrea Gluckman)

Democracy Now! interview with Julia Wright and Paul Ortiz about "How the Elaine Massacre of 1919 Influenced Richard Wright," author of Black Boy and Native Son.

1919-1947: Massacre, Floods, and Cotton

The second period of history witnessed by the walls of 100 Main Street covers turbulent decades of physical and social devastation. However, the seeds are also sown for resilience and rebirth.

Starting with the Elaine Massacre of 1919, there followed a number of apocalyptic events--the Great Mississippi River Flood of 1927, the Great Depression, the Drought of 1930-1931, the 1937 Flood, and the multiple continuing horrors of Jim Crow, not to mention the effects of World War II.

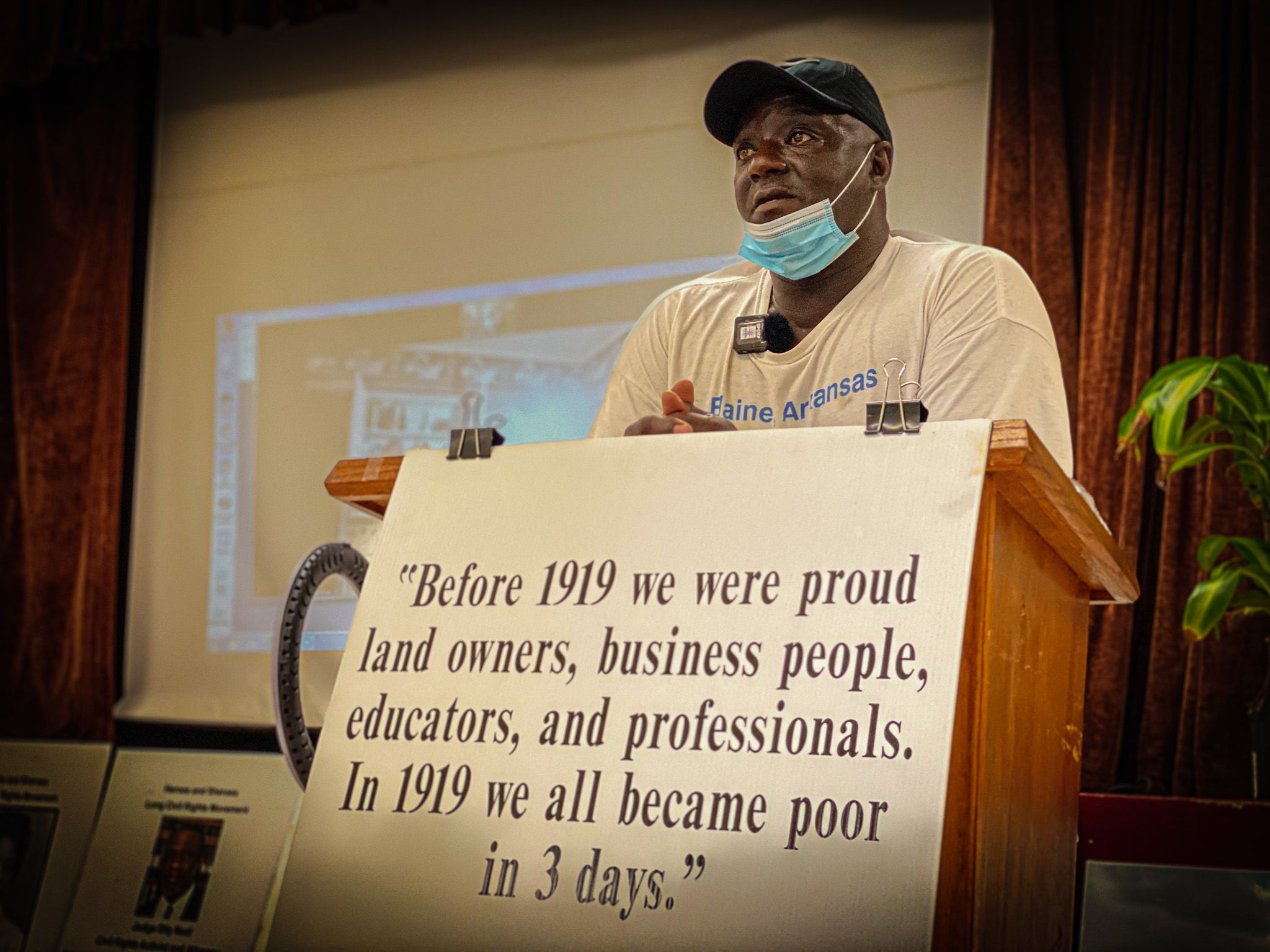

During this period, the prosperity that African American communities had was violently destroyed , as generational wealth disappeared overnight in the aftermath of the massacre, stolen and consolidated by perpetrators of the massacre.

James White, descendant of the Elaine Massacre, speaks to an audience gathered to discuss the Supreme Court case Moore v. Dempsey. The quote on the podium is his. (Photo credit: Andrea Gluckman)

James White, descendant of the Elaine Massacre, speaks to an audience gathered to discuss the Supreme Court case Moore v. Dempsey. The quote on the podium is his. (Photo credit: Andrea Gluckman)

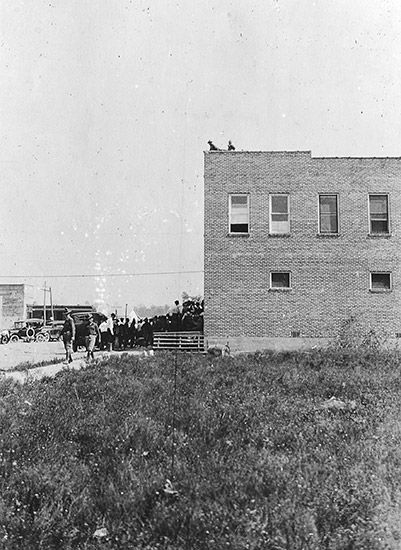

The building at 100 Main Street was front and center in the chaos of these decades. The building served as a drug store, and for a time, as a post office. The train tracks across the street carried history. The same tracks that brought so much life to Elaine each day with commuters and freight now carried bodies of the massacre and National Guard troops.

Similarly, 100 Main Street was inundated with the flood waters of 1927 and 1937, as was all of downtown and much of the surrounding areas. The devastation touched all communities.

World War II left a labor vacuum in Arkansas, which was filled partially by federal prisoner-of-war work camps set up around multiple counties, including Phillips County. The POWs may have been marched past 100 Main Street.

But this period begins with what Elaine has become known for, both in tragedy and in becoming the Motherland of Civil Rights: the Elaine Massacre.

The Elaine Massacre of 1919

“In many ways, this is where it began. Phillips County is the intersection of the long black freedom struggle and it’s also the intersection of white supremacy.”

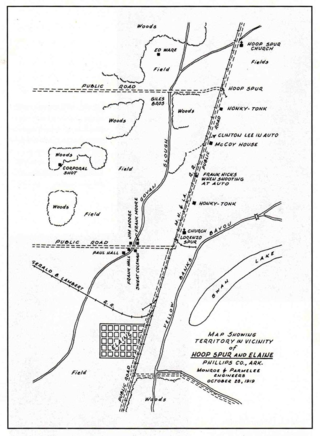

Some say it was the worst race massacre in US history. Some white stories say it started in a Hoop Spur Church where a meeting was being held by farmers wanting fair prices for their cotton. African American oral stories say it started when cotton empire builders headquartered in Helena discovered that black farmers had negotiated fair prices in Boston. The black farmers were readying their raw cotton to be shipped north by rail, where they were guaranteed fair prices, entirely surpassing the cotton companies in Helena trying to cheat them. What ensued was a massacre.

"African Americans in Phillips County, Arkansas, around Elaine, Hoop Spur, were really beginning to get organized. It was the World War I era. The price of cotton was increasing. But most importantly, African Americans were making major gains as landowners in places like Elaine, in places like the Black Belt of Alabama, in northern Florida, all across the South. And the Progressive Household Union in Hoop Spur and in Phillips County, Arkansas, was really coming together with a plan not only to increase landownership among Black farmers, but to begin to farm and market their produce cooperatively. And this was seen as a threat by the white power structure. They mobilized against it."

Unidentified white posse members hunt for black men who had taken refuge in a field in Elaine in this photo taken in late September or early October 1919. (Source: AP/Governor Charles Brough Scrapbook, Arkansas History Commission, File)

Unidentified white posse members hunt for black men who had taken refuge in a field in Elaine in this photo taken in late September or early October 1919. (Source: AP/Governor Charles Brough Scrapbook, Arkansas History Commission, File)

Like around the country, Red Summer massacres meant killing people, burning crops and houses, all to add land to the alluvial empire builders. A cry went out from neighboring Helena, calling for white people from three states to go “squirrel hunting” – code for killing black people--in south Phillips and north Desha Counties. One man from Friars Point, MS said he killed 300 in one afternoon. Men, women, and children killed, bodies burned, dumped in the river, or left in the fields where they were shot. Oral stories tell of mass graves, bodies hauled out in trucks or railroad cars, some dumped in the river. One newspaper man said just under 1,000 were killed. One story tells of children being herded into large oil cans and sunk in the Mississippi River.

Map with details of locations related to the Elaine Massacre (Source: The Arkansas Race Riot by Ida B. Wells-Barnett)

Map with details of locations related to the Elaine Massacre (Source: The Arkansas Race Riot by Ida B. Wells-Barnett)

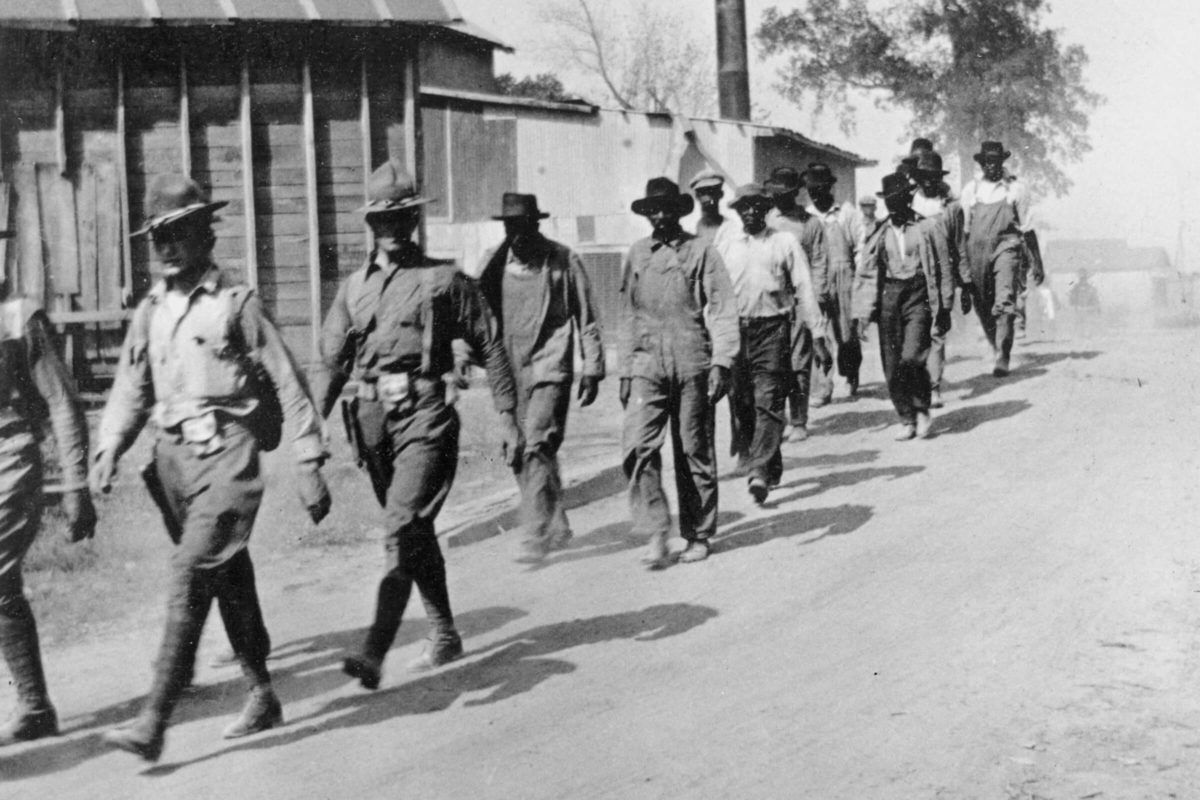

The massacre was falsely reported in the media as a black "insurrection," and the National Guard was called in to ostensibly "restore order," but participated in the killing and arrests of black community members.

"The Army was called in, which makes it a form of state violence at that point, and so you have a machine gun battalion that had just returned from World War I that was based in Little Rock, which is a couple of hours away. They come down and spend five days in a 200-mile radius there slaughtering people. They were innocent people. They weren't armed—men, women, and children. Some people were burned alive in their homes, which is the best way to erase anything. You erase people completely when you do that."

Soldiers place machine guns on top of a building in downtown Elaine in October of 1919. Photo courtesy of Pat Rowe/Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Soldiers place machine guns on top of a building in downtown Elaine in October of 1919. Photo courtesy of Pat Rowe/Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Black men taken as prisoners by the U.S. Army after the Elaine Massacre. (Source: Arkanas State Archives)

Black men taken as prisoners by the U.S. Army after the Elaine Massacre. (Source: Arkanas State Archives)

There are no oral stories of white people who lived in Elaine killing African Americans. All the stories tell of cotton company owners calling for the massacre and sending out others to kill. White people in Elaine, according to oral stories, were hiding and feeding African Americans to save them from death. One example comes from the Mills family.

C. Mills relates the story of how his family hid African American neighbors during the Elaine Massacre.

"I am a descendant of the 1919 Elaine Massacre. Both whites and blacks lost their lives, but mostly blacks. Mobs went to houses taking guns to disarm the blacks. There were no streets back then but dirt roads. So when some of the blacks saw the dirt dust coming, they knew that the whites were coming to take their guns so they hid them."

“I heard that many black people were killed in the massacre. I heard that they didn’t have a decent burial. They just dumped them in places, all in one grave together, and covered over.”

Arkansas Governor Charles Hillman Brough addresses a crowd outside the Elaine Mercantile Co. after the Elaine Massacre.

Arkansas Governor Charles Hillman Brough addresses a crowd outside the Elaine Mercantile Co. after the Elaine Massacre.

After the massacre, many African Americans were imprisoned in Helena or sent to prisons elsewhere. Not one white person was arrested murder or racial terror against African Americans. Instead, African American farmers were put on trial. They were known as the Elaine 12, all tortured and six sentenced to death. Trials were often a few minutes long with no evidence.

The Elaine 12: Alfred Banks, Ed Coleman, Joe Fox, Albert Giles, Paul Hall, Ed Hicks, Frank Hicks, Joe Knox, John Martin, Frank Moore, Ed Ware, and William Wordlaw (Source: Arkansas State Archive)

The Elaine 12: Alfred Banks, Ed Coleman, Joe Fox, Albert Giles, Paul Hall, Ed Hicks, Frank Hicks, Joe Knox, John Martin, Frank Moore, Ed Ware, and William Wordlaw (Source: Arkansas State Archive)

The case of the Elaine 12 went all the way to the Supreme Court – and was won in Moore vs. Dempsey, which determined that the defendants did not receive a fair trial, because the trials were conducted in a lynch mob atmosphere. A number of lawyers were involved, including Walter White, Scipio Jones, and James Weldon Johnson. The case was won in 1923. It took two more years for the prison doors to open.

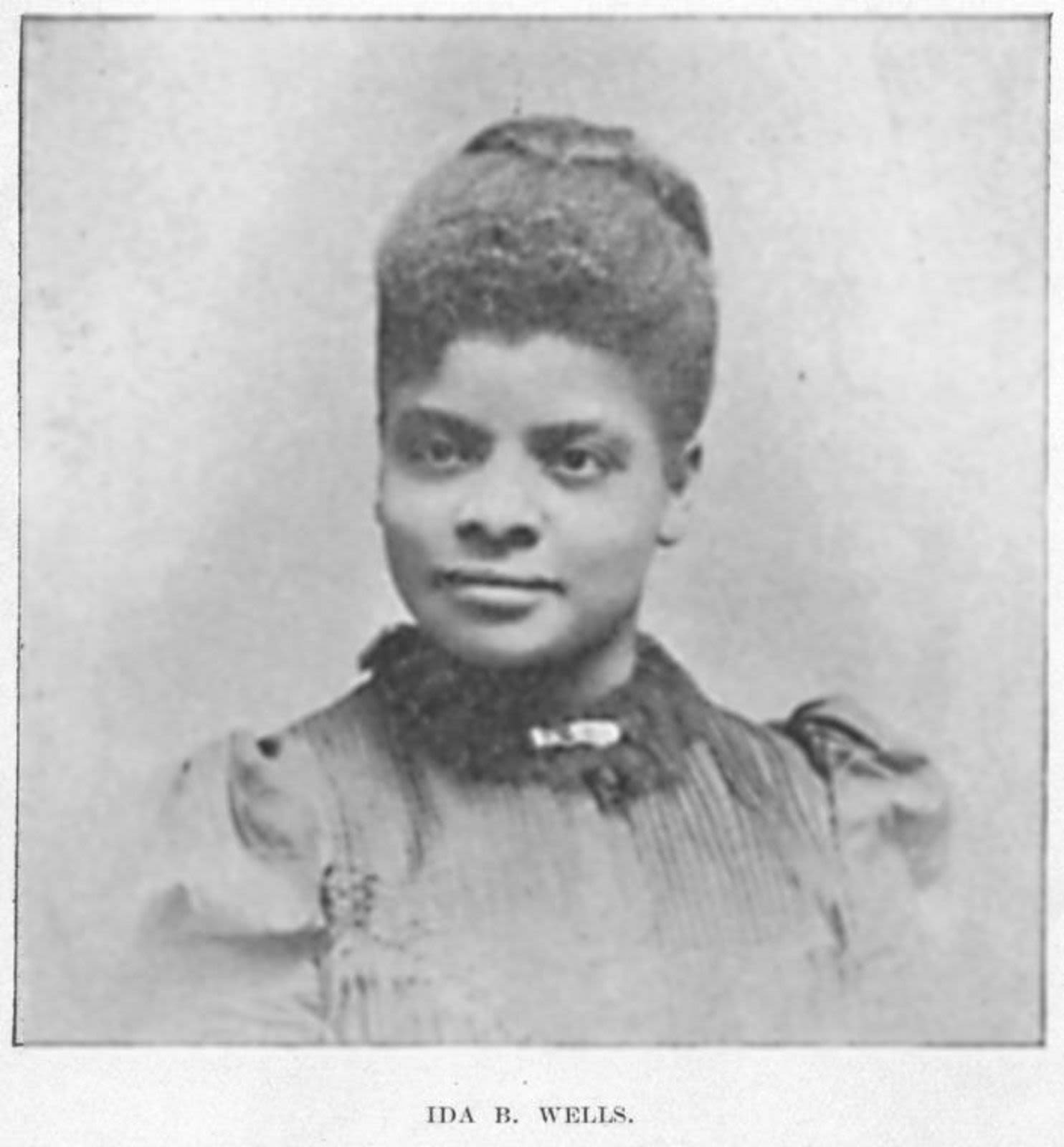

The work of journalist and activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett was essential to setting the stage to save the Elaine 12. Through her investigative and fearless journalism, she was among the first chroniclers of the terror inflicted upon the black inhabitants of Elaine. Her documentation and elevation of oral history of the harmed as evidentiary truth has paved the way for justice work today.

The Elaine Museum and Richard Wright Civil Rights Center sponsored a symposium on the importance of the Moore v. Dempsey decision. Judge Wendell Griffen's keynote connected the dots between Red Summer violence like the Elaine Massacre to the current challenges of mass and wrongful incarceration. He is pictured with Annie Ruth Zachary Pike, a civic leader and activist from Phillips County, as well as the first African American appointee to a state board (who was later appointed to a variety of federal organizations by President Richard M. Nixon.)

Ida B. Wells-Barnett, journalist, suffragist, and co-founder of the NAACP, wrote "The Arkansas Race Riot" after surreptitiously interviewing the Elaine 12. Her investigative work and activism contributed largely to their release. (Source: 1893 book, "Women of Distinction." Public Domain.)

Ida B. Wells-Barnett, journalist, suffragist, and co-founder of the NAACP, wrote "The Arkansas Race Riot" after surreptitiously interviewing the Elaine 12. Her investigative work and activism contributed largely to their release. (Source: 1893 book, "Women of Distinction." Public Domain.)

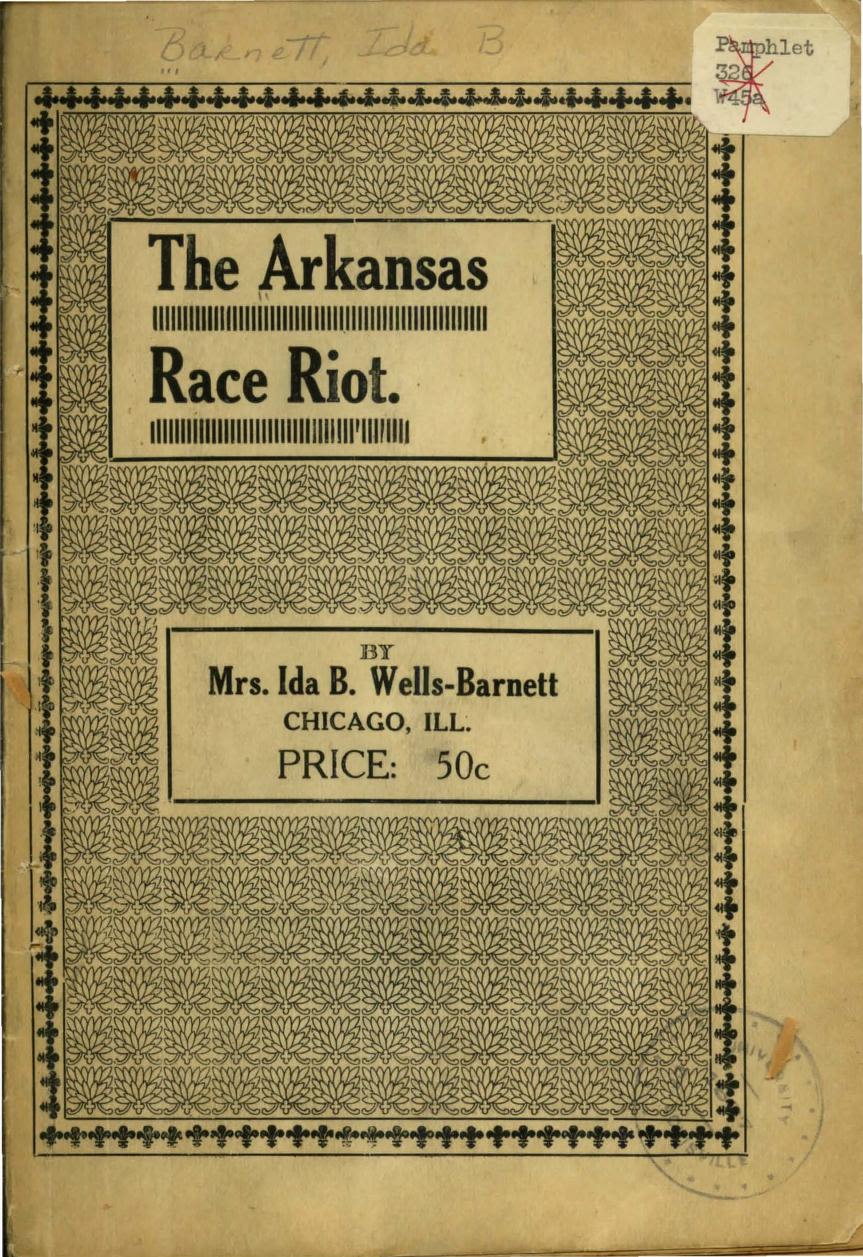

Ida B. Wells-Barnett's "The Arkansas Race Riot" shows that "the riot was a conspiracy by the white men to take the Negroes' cotton and not a conspiracy by Negroes to kill white people" (from original back cover).

Ida B. Wells-Barnett's "The Arkansas Race Riot" shows that "the riot was a conspiracy by the white men to take the Negroes' cotton and not a conspiracy by Negroes to kill white people" (from original back cover).

"The colored men who went to war for this democracy returned home determined to emancipate themselves from the slavery which took all a man and his family could earn, left him in debt, gave him no freedom of action, no protection for his life or property, no education for his children, but did give him Jim Crow laws, lynching and disenfranchisement."

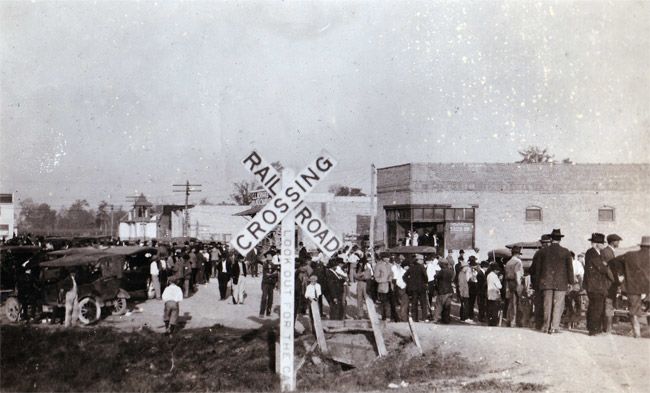

A crowd gathers at the railroad crossing in downtown Elaine in October 1919, waiting for troops to arrive, with 100 Main Street in the background. (Photo courtesy of: Pat Rowe)

A crowd gathers at the railroad crossing in downtown Elaine in October 1919, waiting for troops to arrive, with 100 Main Street in the background. (Photo courtesy of: Pat Rowe)

Legacies of the Massacre

The legacies of the violence of the Elaine Massacre have been passed down through generations of victims and perpetrators to the current day. One of those legacies was (forced) migration from the south to cities in the north and the loss of African American owned land. Bryan Stevenson, founder and Executive Director of the Equal Justice Institute speaks on how these forced exiles of black communities fleeing terror resulted in lost land and intergenerational wealth, as well as a refugee status that prevented integration and support in new communities.

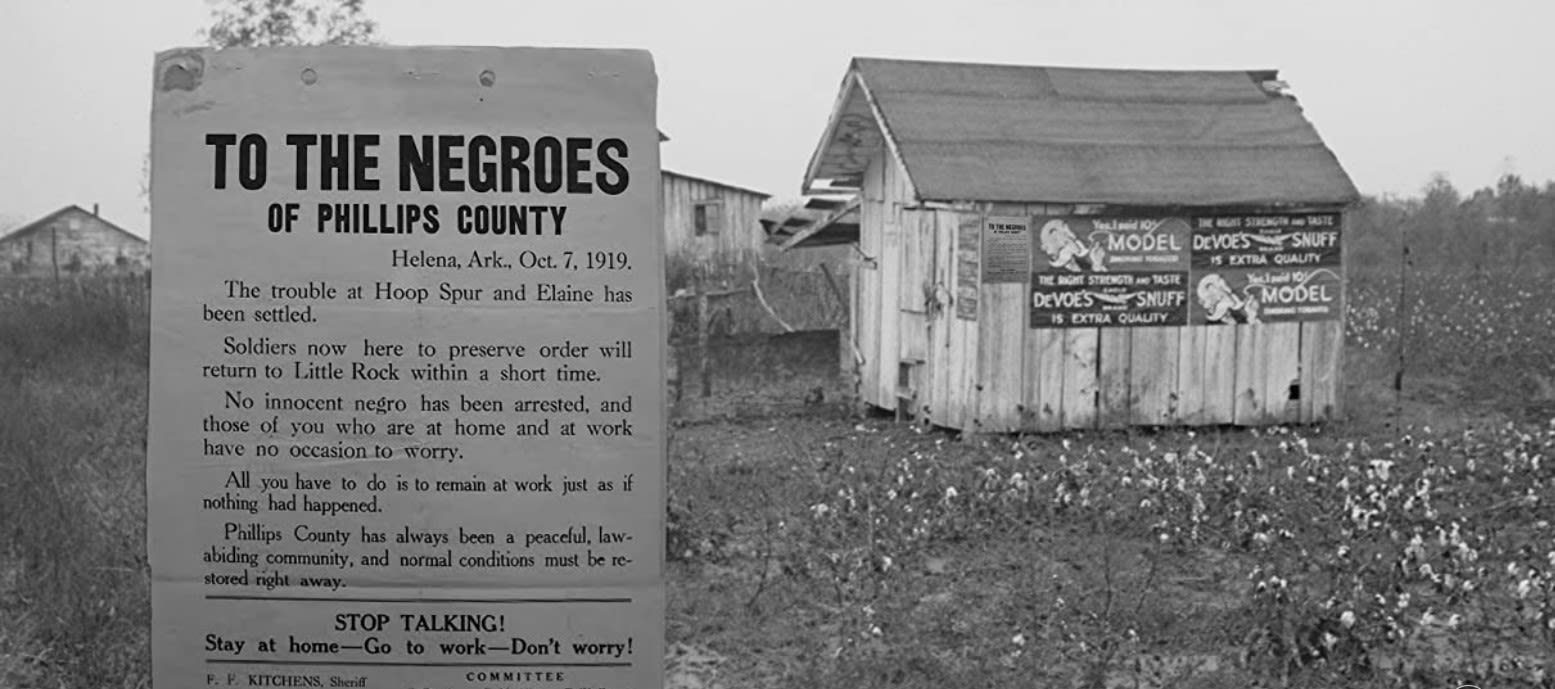

Another devastating legacy of the massacre is that of silence. A deliberate "Hush Mouth" campaign was waged against the black communities in Elaine and the surrounding areas, demanding silence and normality in the wake of the massacre, with the thinly veiled threat of retaliation for failure to do so. That silence has persisted--as a way to protect the surviving families and as a way to bury history.

The "Hush Mouth" campaign had the specific intent to threaten black communities into silence about the Elaine Massacre.

The "Hush Mouth" campaign had the specific intent to threaten black communities into silence about the Elaine Massacre.

“My grandmother was my North Star. She told me everything. And the one thing she did not tell me about is Elaine. This is my heritage, just like it is your heritage. And we need to be sure that it is reformulated, it is reshaped to become a positive part of our history…We must do what we can do to make things right.”

Descendant Linda K. Shelby speaks about her family in Elaine before and after the massacre, particularly of the role that silence played in protecting the family.

“Our utmost desire is that the information stored in the Elaine Museum and Richard Wright Civil Rights Center concerning the 1919 Elaine Massacre will be counted as momentary madness, never to be repeated.”

The Great Floods: 1927 and 1937

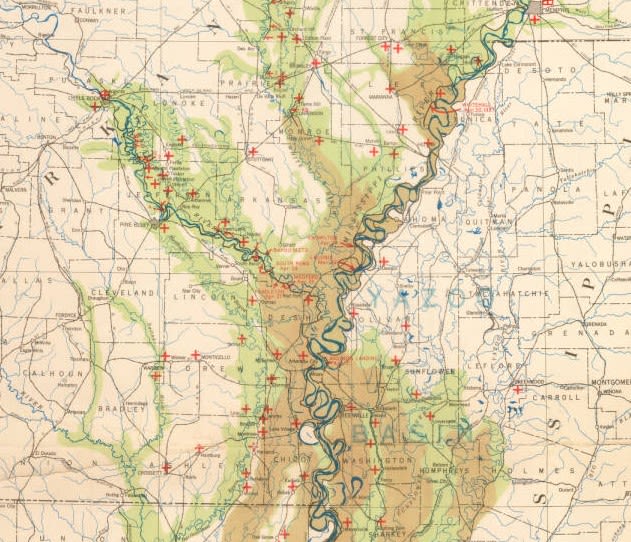

Phillips County is located in the Delta region of Arkansas, where the St. Francis River empties into the Mississippi River, with the White River to the west, along with over 30 lakes and ponds and innumerable creeks, tributaries, and waterways.

Major floods in 1927 and 1937 devastated the farms and the cities of Phillips County. The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 was the most destructive river flood in the history of the United States. Levees that had been rebuilt and improved after earlier floods were unable to handle the water those years. During the flood of 1927, the Laconia Circle levee at Snow Lake broke in six places, leaving the unprotected farms under sixteen feet of water.

Map of the Great Mississippi River Flood of 1927. The red marks indicate the places where the levees failed.

Map of the Great Mississippi River Flood of 1927. The red marks indicate the places where the levees failed.

The Great Flood of 1927 in downtown Elaine. 100 Main Street is the drug store on the corner. (Photo courtesy of: Kyte Collection)

The Great Flood of 1927 in downtown Elaine. 100 Main Street is the drug store on the corner. (Photo courtesy of: Kyte Collection)

Flood waters outside the Elaine Mercantile Co. in 1927. (Source: ArkGIS)

Flood waters outside the Elaine Mercantile Co. in 1927. (Source: ArkGIS)

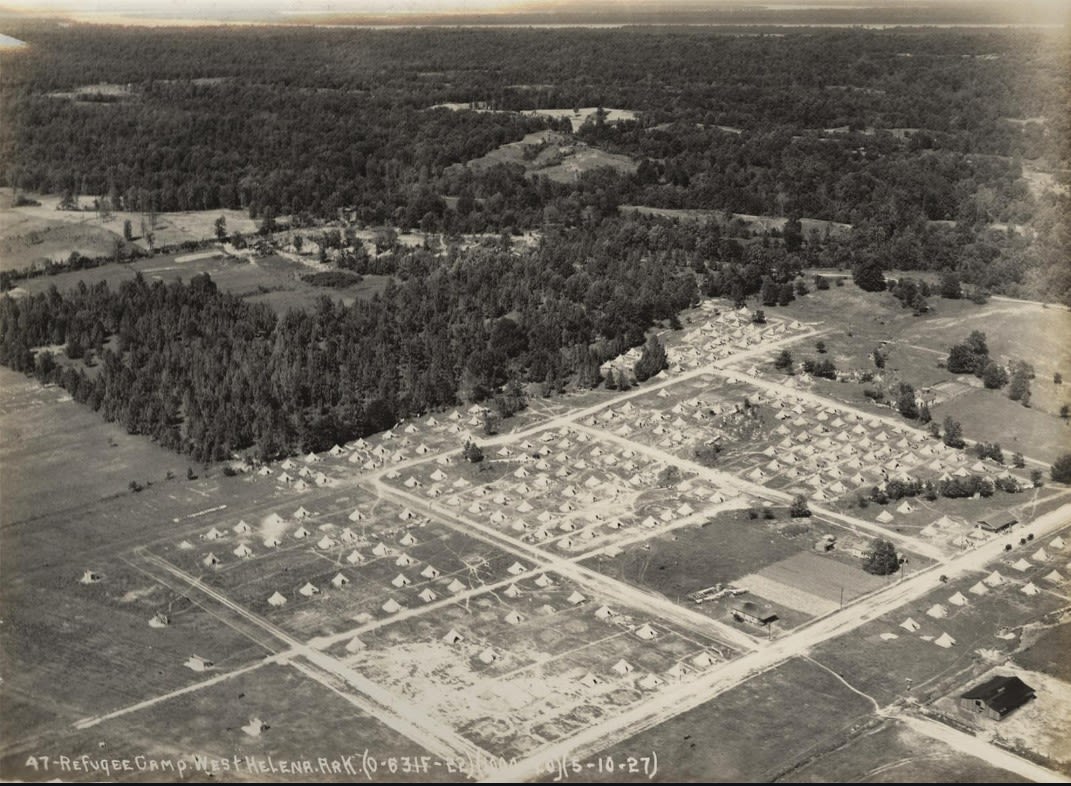

The Red Cross set up segregated tent cities for refugees using army tents. Relief was scant, although Congress was prompted to pass the 1928 Flood Control Act, which placed the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in charge of rebuilding the levees.

Refugee Tent Camp in nearby West Helena (Source: ArkGIS)

Refugee Tent Camp in nearby West Helena (Source: ArkGIS)

View of a drone moving down a levee road in Phillips County, Arkansas. The levees have been essential to protecting homes and farmland and provide a network of elevated roads around the county. (Drone footage: Andrea Gluckman)

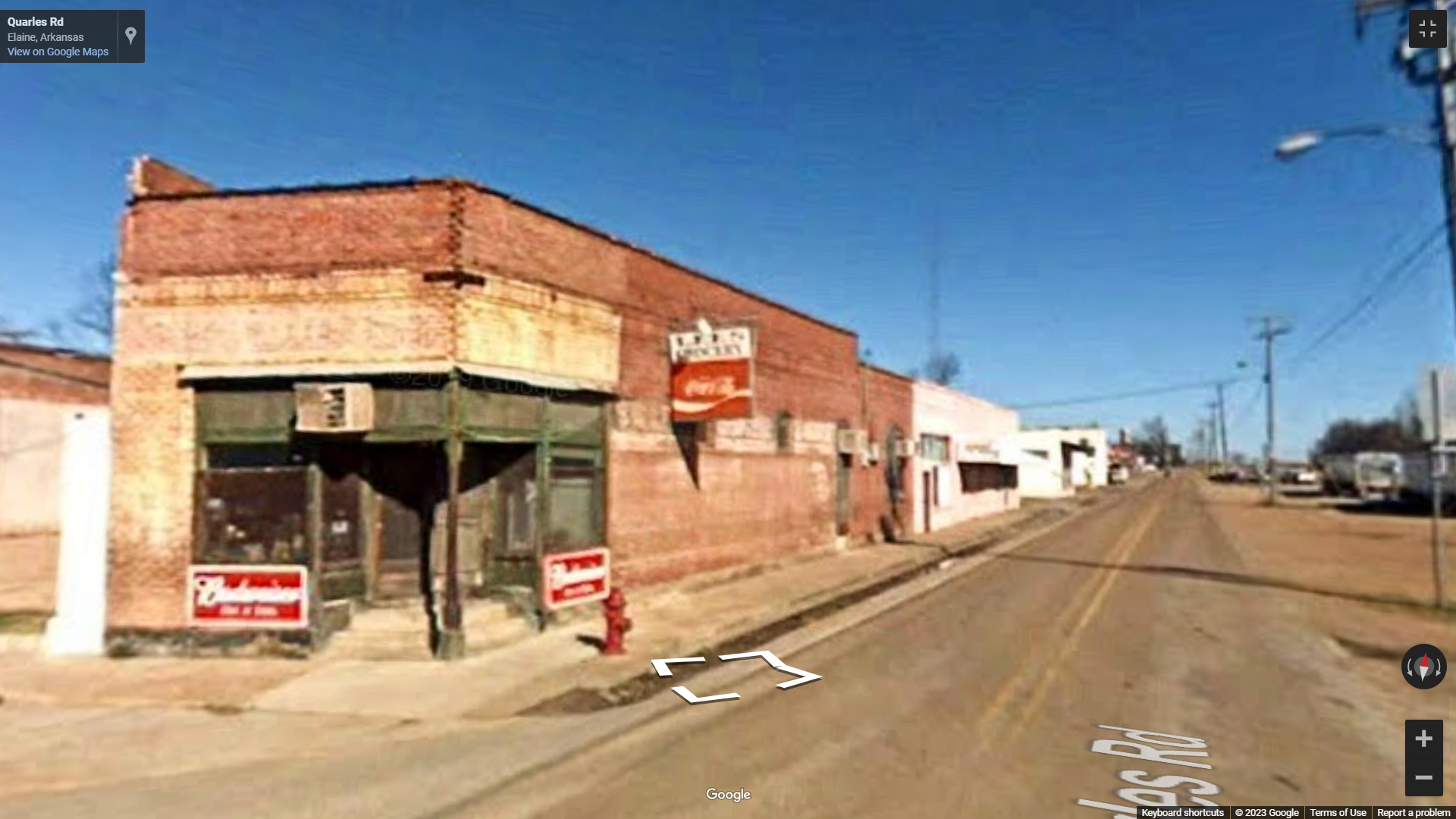

1947-2014: Lee Grocery

A Thriving, Yet Segregated Town and a Store Where Everyone Was Welcome

The oral histories present this period in Elaine as a time of a bustling little town with a movie theater, stores, and doctors' offices. Elaine was the place to be on the weekends, where sidewalks overflowed with people coming to shop, eat, and have fun.

"When I was growing up, I longed to go up there to Elaine. Elaine was happening. When I got to go to Elaine I was so excited. That was the highlight of my weekend."

Black-owned businesses are also a part of those oral histories, including cafe owners, barbers, cobblers, and others.

"Everything that blacks owned, they had to be kind of quiet with it. We had some black businesses."

Lifetime Elaine resident Charlie Brown recreated a map of downtown Elaine during this period, giving a vivid picture of what life was like at that time.

Jim Crow in Elaine

The oral histories also denote the segregation that defined community experiences: whites served in the fronts of restaurants and blacks served at the back or through a side window, a segregated movie theater with white patrons downstairs and black patrons in the balcony, segregated soda counters.

"When I was growing up, there was a large, large ditch. They called it a grudge ditch that divided the whites from the blacks. The blacks lived one one side of town, and the whites lived on the other. And we went to the restaurants, we had to go in the back part, in the alley part...Same with the drug store. We could go buy a Coke or an ice cream, but we couldn't sit down there and eat it or drink it. But the whites would sit at the counter enjoying. The same with the Dairy King. We could go to the window on the outside and order some food, but we couldn't go inside. But later years we could go inside. Later years, we could come across that ditch. Some of us began to move over in their area, and now the blacks and the whites, they are living in the same neighborhoods."

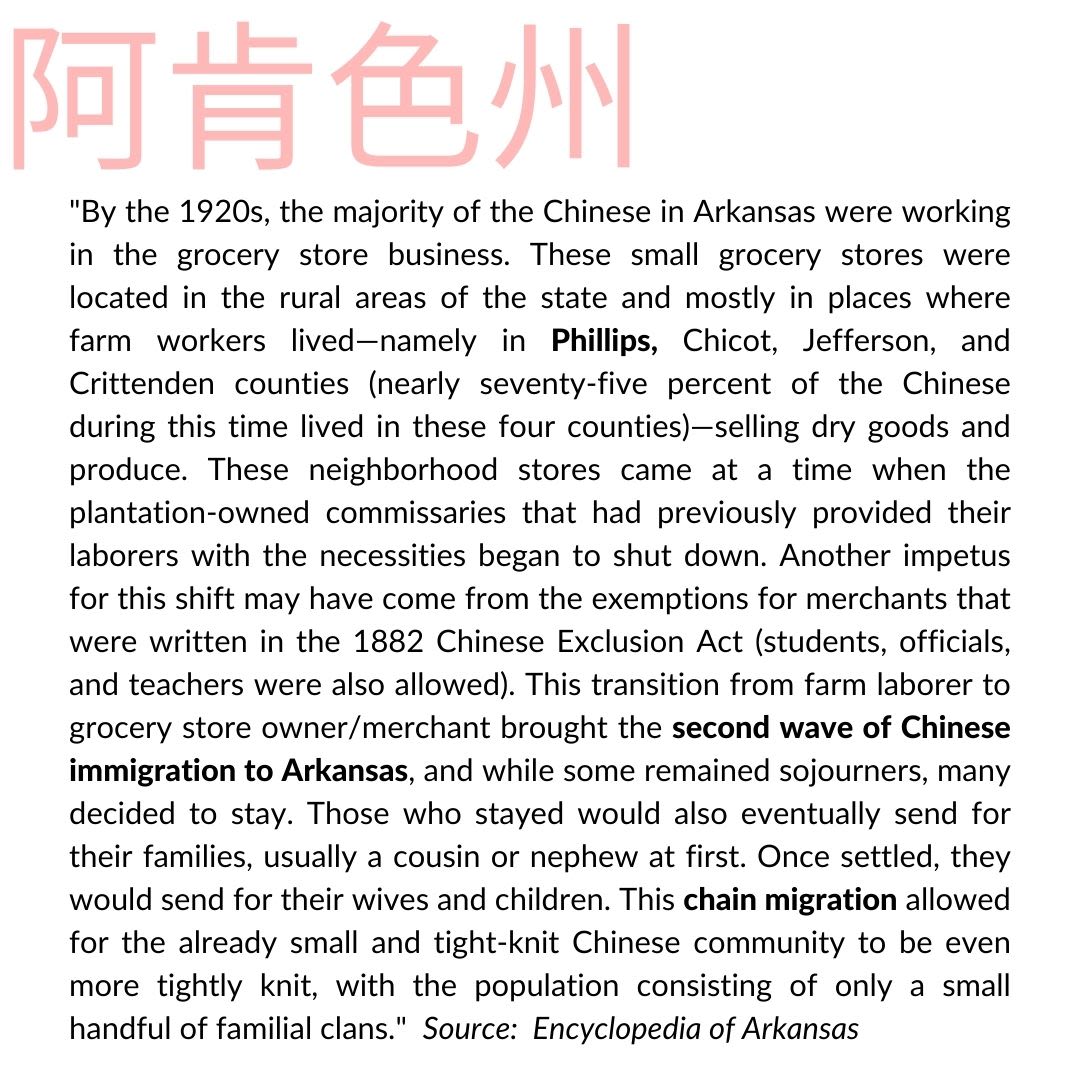

Chinese Families in Arkansas

Chinese families were also affected by a number of discriminatory practices. Arkansas senator C. B. Ragsdale of Arkansas County introduced a bill in 1943 that would prohibit non-citizens from owning or renting property in the state. There was also a proposal to prevent Chinese children from attending white public schools. The Chinese community was in an inbetween space during segregation, not considered white or black.

Descendants of the 1919 Massacre remember when there were five stores owned by Chinese immigrants in Elaine. Now the stores and their owners are gone. Lee Grocery was the last to close. People remember quietly and enjoyably shopping there as the history of plantations, agribusiness, and persistent poverty swirled around it. Inside, it was a friendly place where shoppers were treated equally and fairly. The building itself was bought in 1947 by W.J. Lee, a Chinese immigrant who had heard talk of economic opportunities in the South. W.J. opened and managed the grocery store. The Lee family operated Lee Grocery and lived in the back of the store, as was standard for many storekeepers. The store was later passed on to two of his sons, Seat N. Lee and Kam S. Lee. Seat and Kam operated the store until 2010.

One place that did not practice segregation was Lee Grocery. The Lee Grocery store was described as a place where black customers did not have to "step aside" to allow white customers prioritized treatment. There was a large black clientele that remembers the Lee family as kind, generous with credit, and non-discriminatory.

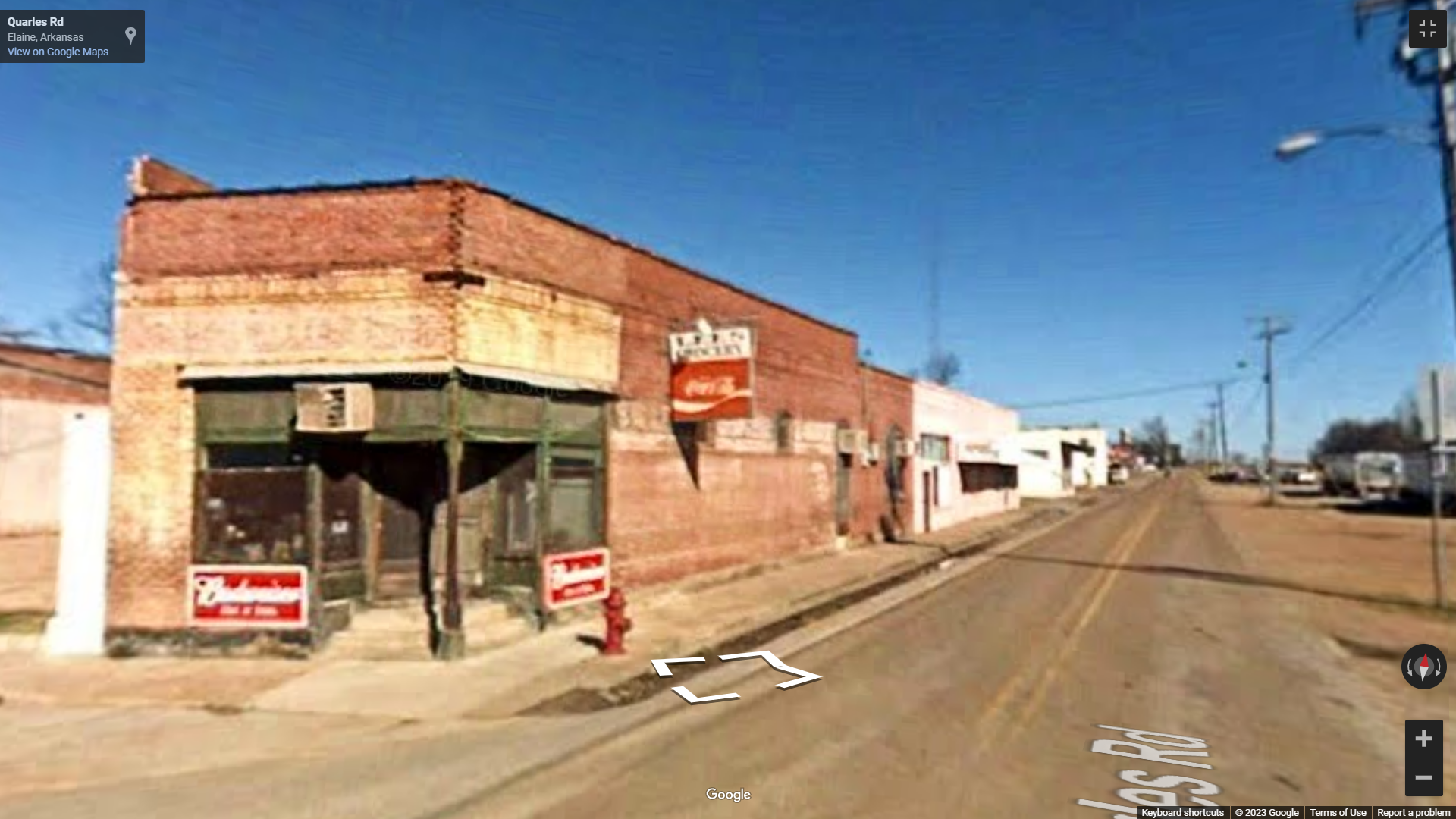

Lee Street Grocery (Source: Google Street View)

Lee Street Grocery (Source: Google Street View)

Lenora Marshall talks about the Elaine of her youth and experiences at Lee Grocery.

Mexican Migrant Workers

Migrant workers from Mexico came to work in the fields from the early 1900s on, but particularly after WWII to work in cotton fields. In the mid 1950s, Refugio Mora's family of 18 siblings came to Elaine, eventually living permanently in the area and working at a variety of jobs.

Refugio Mora speaks to Mary Olson about his Mexican family coming to Elaine.

Stories about Lee Grocery and Elaine

Collected by Lenora Marshall

Viola Watson

I went to the store now and then. I know mostly about home cooking. I came along when we cooked turtles. We used to call them cooties. Cokes cost 5 cents. Loaf bread was cheap. If you wanted land, you would find woods with a bunch of trees and cut you out a spot. If no one made you move, you claimed that as your own land. We would milk the cows, strain the milk, and let it clabber and then churn it to butter. Chopped cotton for 25 cents a day. When we went to church, we had to hook a slide to the mule and get on the slide and ride to church.

Sam Gilmore

Pat Lee’s store was on the corner where the Elaine Museum and Richard Wright Civil Rights Center is now located. Pat’s place of business was packed out with people on Saturdays and rainy days.

The store next to Pat Lee’s Grocery was a café called the Jones Café. The blacks were served food in the back, and the whites were served food in the front of the café. Mr. T.B., a black man, cut hair and repaired shoes in the back of the building while his wife Rose sold food plates in the front. She cooked and served every day like pork chops, beans, and corn bread for 50 cents a plate.

There was a movie theater in Elaine. Even though both black and white went to the movie, they were separated. The blacks went upstairs, and the whites went downstairs. The town was really divided.

Patricia Taylor

I went to Pat Lee’s store to fill my children’s vouchers. Pat and his wife were very nice people. They never showed that they were prejudiced. One thing that bothered me was when I went to the store without my husband and bought food, Pat would make his wife carry that heavy grocery. I would shop there once in a while.

My husband recalls a crowded Elaine. In later years, Elaine was crowded during the Christmas parade. We moved from Helena to St. Louis then back to Ratio. As a young girl, my great grandmother would call to Elaine to the grocery store and tell the Store Keeper (Ned’s Grocery) to let us have candy on her account. We had to get the candy and get out of the store immediately and come home.

Liz Thomas

Pat Lee would allow people to charge food at his store. He seemed to be a fair man. He would hire blacks to help him occasionally. Pat’s family lived in a building in the back of the store. You could purchase bologna and crackers for 5 cents.

Pat had a very calm spirit. We were little children running in and out of the store while our parents were shopping, and Pat would not say a word. My aunt and her friends love to go to Pat’s store.

Johnnie May Rogers

I never shopped at Pat Lee’s store, but I took a woman who is now deceased (Rebecca Mahan) to the store at least once a month to buy groceries. She was 101 years old when she passed. Mrs. Mahan loved to do business at Pat Lee’s because she was treated nicely and she could charge her goods. If she could not pay her bill on time, Pat did not worry about her. He gave her all the time she needed.

Pearl Roy

We visited Pat Lee a few times, and he was very nice. We had very little need to go to the grocery store, because we raised practically everything—cabbage, potatoes, bell peppers, you name it. We had hogs, chickens, even a horse. We owned our own land. Back then I think my father paid $1.67 an acre for land. So we would have to buy meal or flour occasionally. We cooked our own bread, so we only picked up a few times.

Arminta Terry

I could not stay out of Elaine. The streets stayed crowded. It was in the 1950s. Pat Lee’s place was always full of people. The Lee’s store was a place to meet and enjoy other people. I never asked to change anything but I know that some people did.

Nancy Brown

My mother shopped at Lee’s Grocery. She did not ask for a credit account although Pat Lee allowed poor blacks to charge food at his store. My mother mostly cooked her breads and did not eat lots of cold cuts (luncheon meats). We had chickens in the yard and hogs. We also had a garden. My mother canned peaches, tomatoes. When we killed hogs, my mother would make cracklin skins like the chips you buy in a bag. She also used the skin off the hog to cook beans. We had a big potato patch. When we did go to the store, Pat would say, “Get that frown off your face—frown won’t do anything but bring you down.” We have lived in Elaine all of our lives. We do own land both in Elaine and Lake View.

Jerusha Hobbs

The Chinese man on the corner (Pat Lee) was really friendly. Once you start talking with him, you could hardly get away. He had a good personality for business. My friend and I used to park out on the street in front of his business and watch the people come and go. He got good trade. I recall those hardwood floors and I remember those fresh cold cuts. I bought a radio from him and today that radio is like a brand new radio. It plays good.

Charlie Brown

My mother would help Pat Lee with his children (babysitting). He lived in the back of the store building. They were very friendly people. They had two sons and one daughter—Tyrone, Timothy, and Jimmy Sue. Tyrone has become a doctor. Timothy works for the state, and Jimmy Sue lives in Texas. They keep in contact with me, call during holidays. The trade at the store was real good. They knew how to treat people.

Betty Marshall

Elaine was a flourishing and popping town. Movie theater, Cool Spot (black-owned), black-owned barber shop, three black business owners (grocery stores). Four Chinese men had grocery stores and Wades Grocery (white-owned), a skating rink, three clothing stores, two hardware stores, two doctors had their own offices, drug stores, a 5 and 10 cent store. Arthur had a café and dance hall (black man) where Bill’s Dollar Store on Main Street was. The population in Elaine used to be about 2,000. There were 500 students. Charles Dunlap had a dance hall in Elaine.

There were so many people living in Elaine. We had the Red Quarters and the Green Quarters. They were full of houses so close together. So close that you could jump from one porch to another.

Eldun Marshall

I was told that Lee’s Grocery was a store where you could go and shop and socialize. It is unbelievable to hear that you could buy 15 cents worth of cold cuts and could not eat it all. Five cents for a soft drink. I hear that you could chop cotton for $4 a day. The older people spoke of how cheap flour and meal were. I suppose the wages for labor balanced with the prices they had to pay for food and clothing. Pat sold groceries and over the counter medicines.

2014-Present: Decline and Rebirth

The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places on February 13, 2020. After Lee Grocery was sold in 2014, the building at 100 Main Street sat empty, slowly deteriorating in the unforgiving Delta weather.

Picture of the inside of 100 Main Street, between the selling of Lee Grocery to the beginning of transforming the building into the Elaine Museum and Richard Wright Civil Rights Center. (Photo credit: Sean Clancy, Arkansas Democrat-Gazette)

Picture of the inside of 100 Main Street, between the selling of Lee Grocery to the beginning of transforming the building into the Elaine Museum and Richard Wright Civil Rights Center. (Photo credit: Sean Clancy, Arkansas Democrat-Gazette)

Picture of the inside of 100 Main Street, between the selling of Lee Grocery to the beginning of transforming the building into the Elaine Museum and Richard Wright Civil Rights Center. (Photo credit: Andrea Gluckman)

Picture of the inside of 100 Main Street, between the selling of Lee Grocery to the beginning of transforming the building into the Elaine Museum and Richard Wright Civil Rights Center. (Photo credit: Andrea Gluckman)

Current Challenges

Elaine still faces a slew of challenges, much like the rest of Phillips County. There are no schools in Elaine, requiring the kids to be bused a long distance. There are few jobs, unemployment rates are high, and poverty is pervasive. Health indicators place Phillips County at the bottom of Arkansas health--exacerbated by the fact that these rural areas are food deserts, have disintegrating water infrastructure, and are laden with toxins from pesticides. The road (back) to a prosperous Elaine must include a clear understanding of its history.

“The Elaine Museum is an example of reparations…the fact that the museum will be there, that people who come to visit will be able to hear the story from the people who are descended from the people who were harmed, is part of reparations.”

Restoration in Progress sign, outside of 100 Main Street (Photo credit: Andrea Gluckman)

Restoration in Progress sign, outside of 100 Main Street (Photo credit: Andrea Gluckman)

History as the Future of Elaine

In 2017, the building was procured to be eventually transformed into a welcome center for Elaine.

James White, Program Director of the Elaine Legacy Center, initiated the idea of creating a museum to tell the story of Elaine. His idea is to create a people's museum in Elaine, to tell the complex and layered history of all people in Elaine--black, white, Chinese, rich, and poor.

James White stands on the eastern side of the Elaine Museum and Richard Wright Civil Rights Center, which is currently being restored. White donated a piece of his adjacent building so the museum could expand its footprint. (Photo credit: Andrea Gluckman)

James White stands on the eastern side of the Elaine Museum and Richard Wright Civil Rights Center, which is currently being restored. White donated a piece of his adjacent building so the museum could expand its footprint. (Photo credit: Andrea Gluckman)

Work on construction, restoration, and preservation began in 2021. Great efforts are being taken to preserve the historic nature of the building, including preserving original brickwork and design. Renovations are ongoing, during which time the museum continues to offer programming both virtually and on site at the Elaine Legacy Center.

The Elaine Museum and Richard Wright Civil Rights Center is the keystone to rebuilding downtown Elaine through heritage and cultural tourism. James White, Program Director of the Elaine Legacy Center, came up with the idea as a way to preserve and protect the history of all of Elaine's communities and time periods through the development of a "people's museum." History belongs to everyone, just as the museum should.

James White speaks about the idea behind the Elaine Museum and Richard Wright Civil Rights Center.

WHAT THE MUSEUM WILL DO

The museum will take all that the walls have seen and memorialize the history of Elaine and, in doing so, will memorialize the pain and triumph of the history of America. What can America learn from the history these walls have seen?

The building of 100 Main Street will serve as a gateway to the history of Elaine--one part welcoming center, one part gathering area for the community, and one part house of sacred memories of Elaine as told through oral histories and expressed through creative activities. The Elaine Museum and Richard Wright Civil Rights Center will serve as a destination for those on a pilgrimage to better understand American history and work towards an American future of truth and repair. America has much to learn from Elaine and can start by listening to the walls of 100 Main Street.

Fund For Reparations Now Board Member Jennifer Hadlock talks about the significance of the Elaine Museum for reparations work.

“It is so important to have a museum to commemorate the massacre and the struggle against white supremacy in Elaine. This is where a museum most definitely belongs. Historians now really connect the Elaine massacre…with the rise, with the birth of the Civil Rights Movement. If you look at the persistence of black organizing in the Arkansas delta, it is one of the great epic stories of American history.”

Professor Paul Ortiz speaks on the historical connection between the Elaine Massacre, the Civil Rights Movement, and the continuing struggle for justice for all. His experience as the Director of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program has led him to bring his students each year to Elaine to collect oral histories of the descendants of the Elaine Massacre.

The complex history of race and class in the United States manifests in the history of Elaine through the immigrant communities that settle and become integrated into the landscape, the Chinese families, the Mexican families. This museum is a witness to these communities, too, in addition to white communities. The museum should reflect the population and its various histories, including the diaspora.

“Going to a museum in the rural south is not like going to a big city museum…going to places where people are still fighting on an everyday basis for justice, for land, for freedom—that is the most meaningful experience I can introduce my students to.”

"Our obligation is to hear the stories of these people and to listen to what they have to say and to hear what they need. How do they understand repair and how do they understand restitution? "

“Oftentimes the people who have the biggest stake in truth telling aren’t allowed to tell their truth, but are talked over.”

The building at 100 Main Street is being carefully protected, preserved, and restored to reflect the history of Elaine.

The architect's rendering of the vision for the restored building.

"[The museum] is an adaptive reuse of a historic structure, which I love. It's a wonderful location and it wasn't stripped of its historic elements. Everything is there."

Exterior details

Exterior doors and windows

Floor plan

Floor plan detail

Aerial view

For a sneak peek of the restoration efforts, click here.

"History is not something you read about in a book; history is not even the past, it's the present, because everybody operates, whether or not we know it, out of assumptions which are produced only, and only by, our history.”

--James Baldwin

These Walls Can Talk

The Elaine Museum and Richard Wright Civil Rights Center's goal is to be one the of repositories Arkansas Delta culture, memory, and arts. In doing so, 100 Main Street stands to provide the physical gate to prosperity for the area built through heritage tourism. Currently the Elaine Museum and Richard Wright Civil Rights Center is sponsoring educational and artistic programming and is deeply involved in placemaking activities in Phillips County. Through education, heritage, and arts programming, the story of Elaine will continue to unfold, breaking silences.

The Legacy of the Elaine 12 Mural

The Legacy of the Elaine 12 mural will hang on the exterior of the western wall of the Elaine Museum and Richard Wright Civil Rights Center, facing the spot where Richard Wright's uncle Silas Hoskins owned a tavern before he was lynched in 1916. The mural artist Johana says: "It tells the story of resilience and now rebirth of a village ready to build a future of prosperity and justice based on its past. The green leaves on 'the hanging tree' symbolize this determination of descendants of the massacre to create a home for heritage tourism and to end poverty and the glass ceiling of the welfare system."

Mural artist Johana stands in front of The Legacy of the Elaine 12 that will be installed on the exterior western wall of the Elaine Museum and the Richard Wright Civil Rights Center. In addition to the Elaine 12, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Richard Wright, and descendants of the massacre are pictured. (Photo credit: Mary Olson)

Mural artist Johana stands in front of The Legacy of the Elaine 12 that will be installed on the exterior western wall of the Elaine Museum and the Richard Wright Civil Rights Center. In addition to the Elaine 12, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Richard Wright, and descendants of the massacre are pictured. (Photo credit: Mary Olson)

Arts programming of numerous genres continue to be underway, from photography to drum lines to West African dance. The Elaine Museum seeks to enrich and elevate the creative work of the people of Elaine and the Elaine diaspora through the platform of the museum.

The work of the Richard Wright Civil Rights Center will focus on education, activism, and partnering with other organizations to advocate for justice and prosperity for all in Elaine. The building seeks to be a gateway to the past, present, and future of Elaine and the greater Arkansas delta.

"History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage, need not be lived again."

“Just the idea of those children, who are survivors, bringing the soil, the memorial soil of my own great-uncle [Silas Hoskins], was like the closing of a circle. And it made me think a lot about intergenerational trauma and how it’s handed down, and how it’s prevented from being handed down, by silence. And what struck me…is that they [descendants of the Elaine Massacre] were all breaking that silence. They were speaking their own narratives…Everybody was breaking through their own silence with their own narratives.”

Edlun Marshall, descendant of the Elaine Massacre, speaks about hope for the future.

What can one building teach America? How to hope, survive, thrive, and rise.

Annie Ruth Zachary Pike is a farmer and community activist from Phillips County, Arkansas. She was the first African American appointed to a state board and to run for state elected office. She was appointed to various state and federal boards in the 1960s and 1970s, becoming a fixture of the Republican Party. Ms. Annie has been recognized numerous time for her tireless efforts in public service. She still lives on her farm in Marvell and continues to fight for the underserved.

"We have had to endure many things. But still we rise."

DEDICATION

These Walls Can Talk is dedicated to all Descendants of the Elaine Massacre--past, present, and future--who are keeping truth alive by sharing their stories and the stories of their families.

THANK YOU

The Elaine Museum and Richard Wright Civil Rights Center would like to thank the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Trust for Historic Preservation for their generous support of this project.

We would also like to thank Lenora Marshall and James White for collecting stories from other descendants with such care.

We would like to thank Julia Wright for sharing her family stories with us and remembering and elevating Elaine.

Thanks to Jennifer Hadlock, Paul Ortiz, Nan Woodruff, Faye Duncan Daniel, Mary Olson, and Andrea Gluckman for the research, writing, and design of this project.

We thank Edlun Marshall for giving voice (literally) to the video portion of our project.

And most of all, thank you to the people of Elaine and Phillips County, who shared their stories and their time, including: Derome Bobo, Charlie Brown, Nancy Brown, Faye Duncan Daniel, Sam Gilmore, Elvin Harris, Jerusha Hobbs, Bernita Scaife Glass, Betty Marshall, Edlun Marshall, Refugio Mora, Johnnie May Rogers, Estella Glass Ross, Annie Zachary Pike, Pearl Roy, Linda Shelby, Patricia Taylor, Arminta Terry, Liz Thomas, and Viola Watson. All full stories archived at the Elaine Museum and Richard Wright Civil Rights Center.

A special thanks to the board of the Elaine Legacy Center: Faye Duncan Daniel, President; Lenora Marshall, Vice-President; Bertha Glasgow, Treasurer; and members Mary Olson, James White, and Edlun Marshall.

Exhibit created by Andrea Gluckman of Aspexi Images. Text, images, and videos protected by copyright.